An honest account of the fun and frustration involved in growing up with twin brothers who both have FASD.

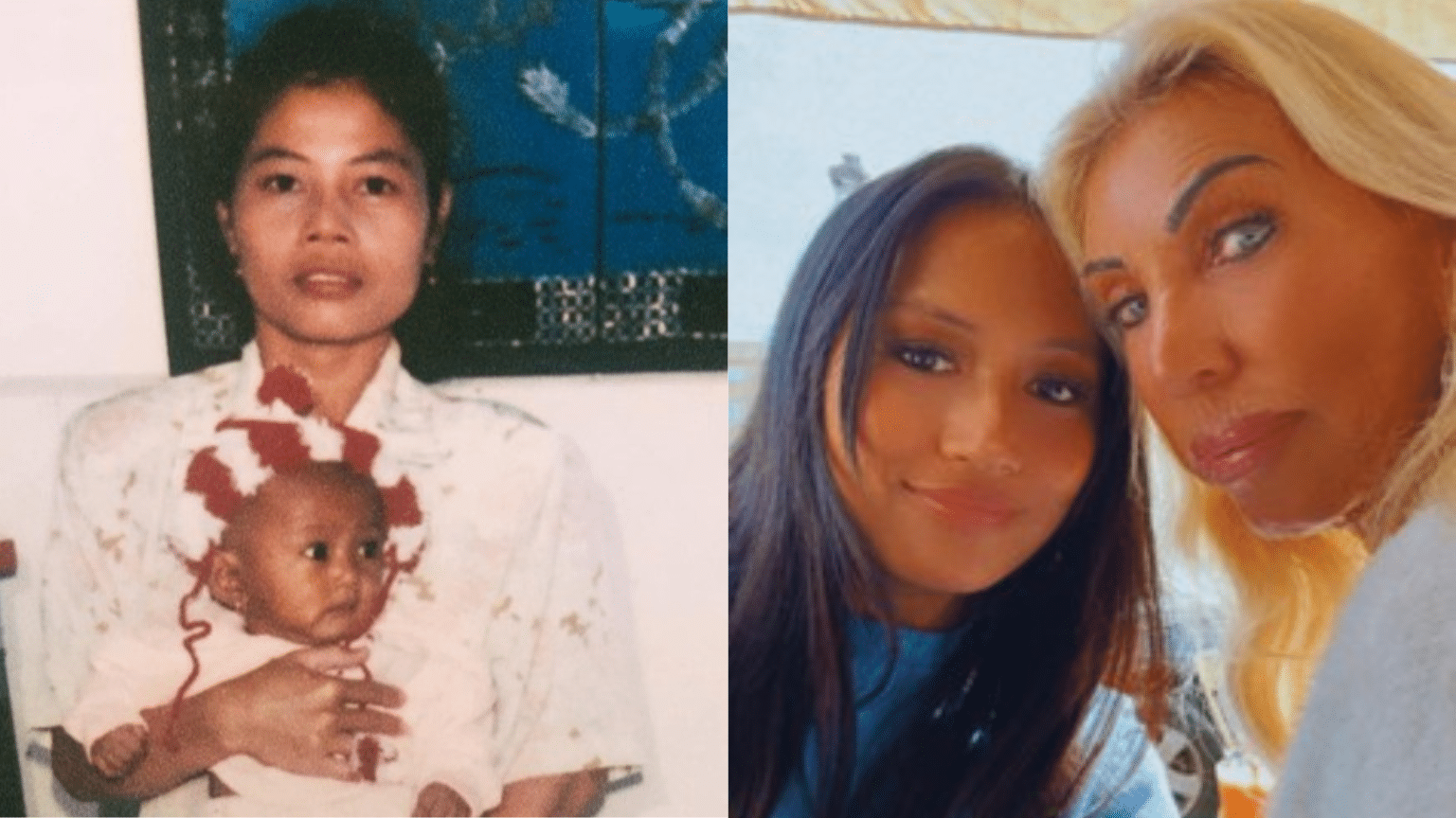

When I was in kindergarten, my parents adopted two-year-old twin brothers. They brought with them a double-dose of both love and of calamity.

On the spectrum, both boys were easily diagnosed as “severely affected.” The first few years are a bit blurry, but I do remember their favourite activities always involved water: sinks, toilets, garden hoses, puddles and ponds…. It didn’t matter how dirty the water might be, if they got the opportunity, the boys were in it. This often came without warning, and always without a sense of cause and effect.

Welcome to the world of FASD! It took them years to realize that if they stuffed towels down the toilet and flushed, there would be repercussions, both immediately (when the toilet overflowed) and long-term (when Mom discovered the mess)!

They were a resourceful little pair. Glenn was the brains of the operation, while Will was the brawn. Glenn often sent Will out on decoy missions and would then declare, ”Look what Will did, Mom!” before scampering off to bring his own havoc down upon the household.

While they delighted in giving our parents grey hairs, the boys definitely had their share of challenges. Both were diagnosed with hearing impairments, and Will’s ear problems were so severe (as was his inability to process pain) that his eardrums would often burst from his frequent infections before he was able to indicate that he was in any kind of pain. Food was an issue, as were the disapproving eyes of certain neighbours. Though they ate more than an average high school football team, both boys simply could not hold any weight. Glenn needed a feeding tube until his release from hospital, and both boys wore toddler clothing (held up by baby-sized belts) well into the primary grades. Glenn–always entertaining, but not always truthful–once told his elementary school teacher: “I’m so skinny! Look at me! Those parents don’t feed me. All I had for dinner was a couple of beans!” Fortunately, the teacher knew better than to call the Ministry on us. Earlier that year, Glenn had falsely accused her of beating him with the spatula his class had used to make green milkshakes on Saint Patrick’s Day.

Though they played well together, both boys had challenges understanding family roles and anything in the abstract realm. In the grocery store line, Glenn proudly introduced his brother as “my beautiful wife!” Will insisted for years that he was going to be a train when he grew up. Often, our home was a madhouse. One day the boys’ toilet stopped flushing, and Dad found 14 toothbrushes when he removed the malfunctioning toilet. When interrogated, Glenn confessed but felt exasperated: “How do you expect me to go my whole life without flushing toothbrushes down the toilet?”

The madness continued through the years. Threats to leave home are common among teenagers, but the FASD spin amounted to the following threat: “We’re going to World War 1, and we’re never coming back!” Thankfully, they never found their way to the Great War, and they soldiered on and made their way in life.

Sometimes, FASD reared its ugly side and left our family feeling inept, angry, and frustrated. By the age of 12, I’d learned to lock up my purse if I wanted money the next day. The boys had no idea of the value of a dollar or what it meant when they took a few coins (or an entire pay check’s worth of twenties) out of Mom’s or sister’s purse. They lost expensive coats on a weekly basis. They lost shoes or threw them out the car window. They unbuckled their seat belts on the highway, they shredded mattresses, and destroyed toys. When they reached the teenage years, I learned to lock and bar the door in case the boys decided to invade the bathroom while I was showering. I love and cherish my brothers beyond measure, but sometimes their antics were too much even for this big sister. Glenn watched a cartoon about vampires and decided he wanted pointed teeth. He spent the next week biting down on a metal bar on the school bus, and every bump they went over contributed to the deterioration of his front teeth. He didn’t get the incisors he was after, but my parents did get a huge dental bill.

We held a garage sale when the twins were 10 years old. The boys were disappointed that their backpacks weren’t selling, so they emptied our homemade cash register, filled their packs with over $300, and sold them for 50 cents each to some horrible person that willingly took advantage of their crazed but well intentioned sales tactic.

Though they have come a long way since the days of vampire teeth and money-losing garage sales, the road ahead is filled with challenges. After high school, both twins expressed a strong desire to leave the nest.

Because of the severity of their diagnosis, however, neither Glenn nor Will could succeed without supports. My parents tried to find a balance that would keep their adult children safe and nurtured without squashing their dream of independent living. The boys moved in with our older sister, and had their own kitchen and living area in the bottom half of her house. Living semi-independently gave them a sense of accomplishment while still remaining a part of a larger family.

The legacy of FASD will always be with them, and has had a lasting effect on our family’s day-to-day existence. Their arrival shifted the focus from evenly distributed attention between all the kids to merely surviving and enduring the boys’ behaviours. While they struggled to make their way, we adapted our behaviours and strategies to try and anticipate whatever antics the FASD mind might come up with next.

As a sibling, my experience with FASD has its fair share of rose-coloured shading. The behavioural, academic, and social legacy of FASD did not spark the worried conversations and sleepless nights I know my parents endured in spades. As an older sibling, I either didn’t notice, or it didn’t faze me when they repeated kindergarten, were placed in resource rooms at school, were left off the invite list to every birthday party, or were teased and bullied on the playground. I didn’t have to sit through medical assessments, confer with social workers, or plan out the lives of my brothers when it became clear that their path would not mirror those of their older siblings. Much to their credit, my parents did an excellent job of maintaining normalcy in the wake of FASD, and shielding all their children—not just Glenn and Will—from the full impact FASD had on every aspect of our lives.

Even today, the boys struggle with relationships, day-to-day routines, and finding their place in society. They know the mark FASD has left on their lives, but they don’t hold a grudge against the diagnosis. To their credit, it was never a crutch, even during the tumultuous teen years. FASD is as much a part of their daily existence as living and breathing. But it does not define them; the twins are so much more than their FASD label. They are loved and valued members of our family, with so much to offer and so much to teach us—even if they never stop flushing toothbrushes down the toilet.