An adoption reunion can answer many questions. It can also change an adoptee’s life in unexpected ways.

When she packed her birth certificate, some cherished photographs, and set off, Sevdin MacDonald hoped they might provide valuable clues that would lead to her lost family in Romania.

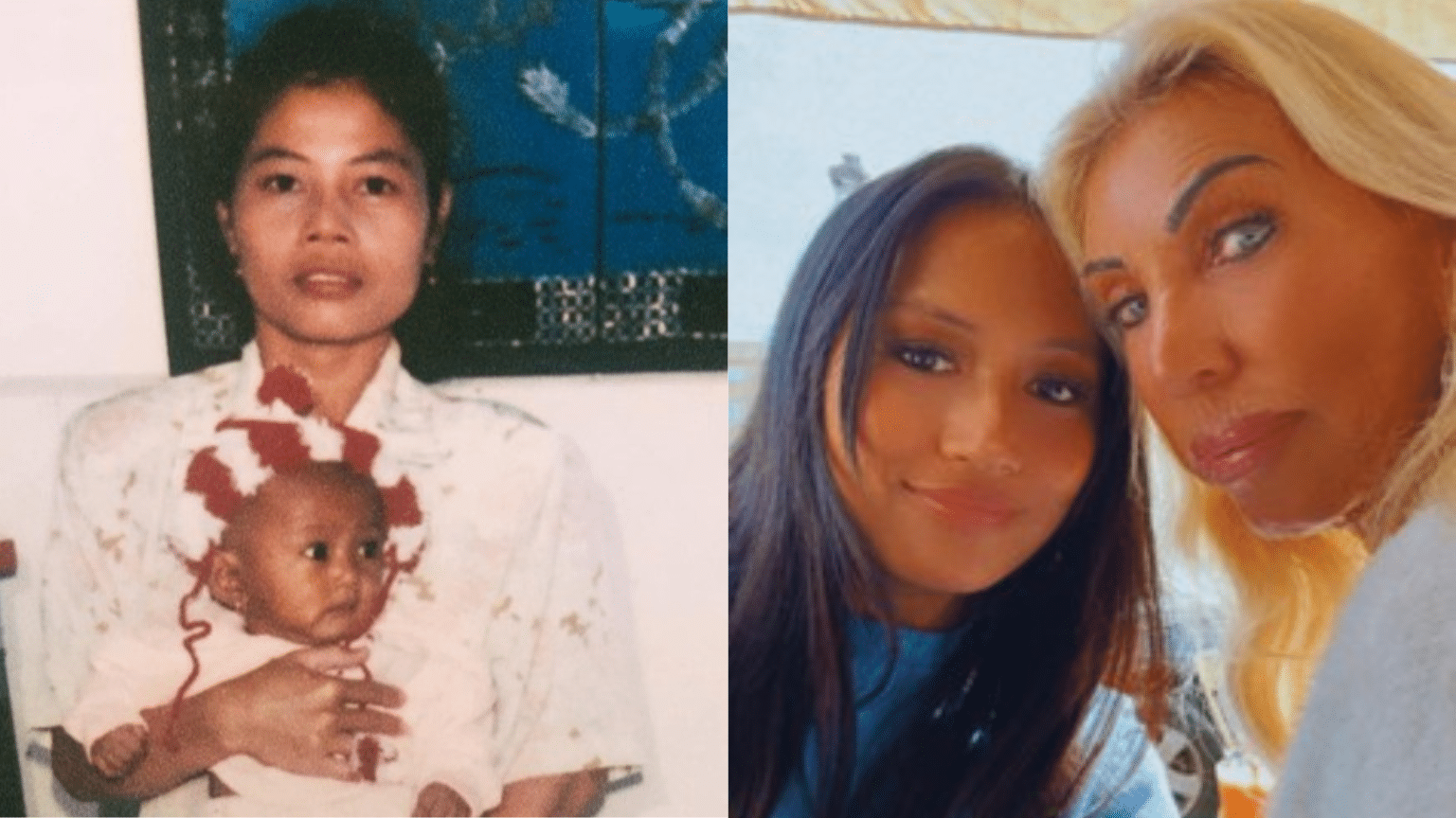

Sevdin was adopted from Romania at two-and-a-half years old, and, as far back as she can remember, she dreamt of returning there to find her birth family. Sevdin’s birth parents are Roma—commonly called gypsies in most of Europe. Many Roma are not registered with local authorities and can be hard to track down.

Sevdin’s adoptive parents, Denise and Brian MacDonald, always promised that they would help her realize her dream. True to their word, they accompanied Sevdin when, in 2008, she set off to work on a Habitat for Humanity project in Romania. Shortly after the family arrived, Sevdin asked the Habitat for Humanity representative for advice on finding her family. It turned out to be much easier than she expected.

Just two days later, the local police gave Sevdin the name of a village only a two-hour drive away. Denise thinks that because one of Sevdin’s birth sisters has a developmental disability, and the family receives some government support for the child, it made it easier for the authorities to locate them. The next day, accompanied by a translator, Sevdin, Denise, and Brian embarked on a journey they’d waited to take for 17 years.

Mixed emotions

Sevdin recalls a mixture of joy and nerves as she drove toward the village. “My birth family didn’t know we were showing up. We had no idea how we would be greeted, or what we would discover,” she recalls. Denise had similar mixed feelings: “We could have found anything,” she says. She had good reason to be concerned.

Most Roma live in medieval type poverty, in ramshackle homes with no running water or electricity; few are able to find employment. Discrimination against the community is widespread. It was clear that the MacDonald family would be encountering a culture and lifestyle drastically different to the one they were accustomed to in Canada. Despite this, Denise recalls saying to Brian as they approached the village, “Who else does this? Who else gets to do something like this?”

Culture shock

When they arrived at the village, Sevdin’s birth mother recognized her daughter immediately. She ran towards Sevdin embraced her, and told her that she had thought about her every day since she had left.

That day, Sevdin met eight of her ten siblings. “Our reunion was as good as I could have expected. After seeing them, I feel like I am part of them. I have two families now,” says Sevdin. Looking at people who looked just like her was also a novel and moving experience: “I look like my dad,” she explains, “As someone who grew up my whole life without people who looked like me, it was very meaningful.”

Sevdin did find the living conditions in the village upsetting. “There was no running water, food was scarce, and there were children with no shoes and some kids were running around naked,” she recalls. “Though the family was extremely poor, it was so positive to see that Sevdin’s birth parents were still together and her brothers and sisters were well,” says, Denise.

At the end of that short visit, Sevdin’s birth mother asked if she could help the family and Denise, Brian and Sevdin wanted to respond. Money was an obvious option, but they had been advised against that—there were addiction issues within the family and community, and it was felt that money would not be the best option—they would have to find an alternative.

Throughout her childhood, Denise and Brian had talked to Sevdin about the conditions of most Roma families, Roma culture, and the problems Roma face as sensitively and truthfully as possible, so she had expected some of what she saw. However, when Sevdin returned to Canada, she felt troubled and spent time trying to figure out how she could help—she even called Christian aid agencies to see if they could assist her family. Clearly it was painful to return to the comfort of life in Canada knowing that her birth parents and brothers and sisters struggled to eke out even the bare necessities. They didn’t even have windows in their ramshackle home. “It was very difficult. Sevdin started to understand the limitations of what she can do for her family,” explains Denise. “She wanted to scoop them all up and bring them to Canada. We have try to work out what we can do, not just what we want to do.”

Delayed reaction

The impact of the visit hit Sevdin hard. She recalls how she felt when she came home: “I was angry; I felt lost; I didn’t feel like being sociable with friends.” Reconciling the circumstances of her birth and adoptive families was not easy, and it’s clear Sevdin is still trying to deal with it. Processing the fact that, though she had been under the impression that she was the youngest sibling in her birth family, she actually has eight younger brothers and sisters, has also been tough. This fact changed Sevdin’s previous understanding of her adoption: “I thought I was the youngest child, then I find out I’m not. It made me wonder, all over again, why I had been adopted—why was it me?”

As the months passed, Sevdin’s desire to see her family again, and to help them, never abated. So, with her parents’ support, she decided to sign up for another Habitat for Humanity project in Romania. After that, Sevdin says, she immediately felt happier.

In 2009, when Sevdin returned to the family village, she arrived with three large bags of clothes and four bags of food. This second visit was easier than the first—there were far less surprises. Sevdin met her two older sisters and made a special connection with her 14-year-old sister, Smeiza. “She taught me to say, ‘I love you’ in Romanian,” explains Sevdin. During this second visit, Sevdin felt more relaxed and calmer. But because the people that accompanied her clearly felt worried about safety, Sevdin could only stay for 15 minutes. “I was quite angry. They were my family. They weren’t going to harm us,” she insisted. Speaking with her birth family was one of her biggest frustrations. Sevdin says not being able to talk to them in Romanian is “driving her nuts.”

Sevdin noticed that since her last visit her birth family’s home had windows and a television. She thinks that they may have sold some of the clothing and toys she mailed to them after her first visit to pay for these items. She points out that, if that’s the case, they had not used proceeds of the sale to buy alcohol.

Wanting to help

Though she is thrilled that she has so many younger siblings, Sevdin now worries about their future. Knowing that Roma children have to grow up faster than Canadian children, Sevdin wants to build a relationship with her younger siblings sooner rather than later. It’s common for young Roma girls to be married in their mid-teens, often to older men, and to have several children in quick succession. Sevdin particularly worries about the fate of Smeiza, her fourteen-year-old sister, with whom she’s feels a tremendously strong emotional bond.

Now back in Canada, Sevdin wants to return to Romania, maybe for a much longer period. Clearly, Sevdin doesn’t just want to respond to her birth family’s needs, she wants to explore how she can contribute to the Roma community in a broader sense. Sevdin particularly wants to work on programs that encourage Roma teens to work and reach their potential. She’s now working hard to save money for another trip.

When Denise MacDonald talks about her daughter’s reunion with her birth family, a reunion she always fully supported, her voice falters and, for a few moments, she can’t speak. She explains that she is full of joy that Sevdin has met her adoption reunion across boarders family, but it’s clear that this joy may be mixed with worry about what happens next and how Sevdin’s obvious desire to deepen her relationship with her family will unfold.

The nature of reunion

A reunion of this nature brings about strong emotions in all involved and there can be much to adjust to for the adoptee, his or her adoptive parents, and for birth family. As is clear from this story, reunion is a process not a one-off event—even when the parties involved are separated by thousands of miles, language barriers, and vast differences in culture and life circumstances.

One of the factors that made this reunion easier was that Sevdin was supported by her parents and, over the years, they educated her about what she might expect and experience once she found her family. However, no matter how hard an adoptive family tries, in a formerly closed adoption, reunion will always involve the unexpected, it will unleash previously hidden emotions, and it will spark new feelings, relationships, expectations and desires. Though these may be challenging, for many adoptees not knowing their birth family and roots is just as hard. It’s clear that Sevdin’s life has been changed by her reunion—as indeed her adoption fundamentally changed her life 17 years ago.

| Adoption reunion across boarders • Support your child if he or she expresses a desire to find his or her birth family—it is not a rejection of you—but the natural desire of many adoptees. • Ask your adoption agency for advice and tips. Ask if they know of other families who have done an international search that they could put you in touch with. Call AFABC—we can link you with other families. • When searching for information about your child’s birth family, you may initially be told that nothing is available. Don’t accept that. Persist in exploring new avenues to find information. • Adoptees often have memories that could provide clues as to their past; explore those memories with them. • Adoptees often construct a vision of their birth families—without realizing it themselves. Expect some grieving when they discover that their story isn’t what they expected. • Make sure your child is educated about his or her birth country, the reasons children may be adopted, the economy and culture. • Think through all possible outcomes of a search—positive and negative. The negative are not reasons not to go ahead, but they need to be considered. • It’s possible that if you find your child’s birth family, they may ask for financial assistance. Consider how you would respond. If you uncover siblings, consider how you would respond. • If you go ahead, and you’re concerned about your privacy, consider using an intermediary to communicate with birth family. Research any intermediary with great care. • If you visit your child’s birth country, it’s critical to find a contact who knows the culture of that country and North American culture—that way they can navigate you through the cultural expectations of both you and the birth family. • Consider that the later you leave a search, the less chance information will be available. |