Tim Windle lives in Langley, where he’s a leader in FASD advocacy and education. In this interview, Tim describes the difficult but ultimately successful process of identifying, advocating for, and creating the supports his daughter with FASD needed to reach her potential and live safely and successfully in the community.

Can you tell us a bit about your family and your experience with FASD?

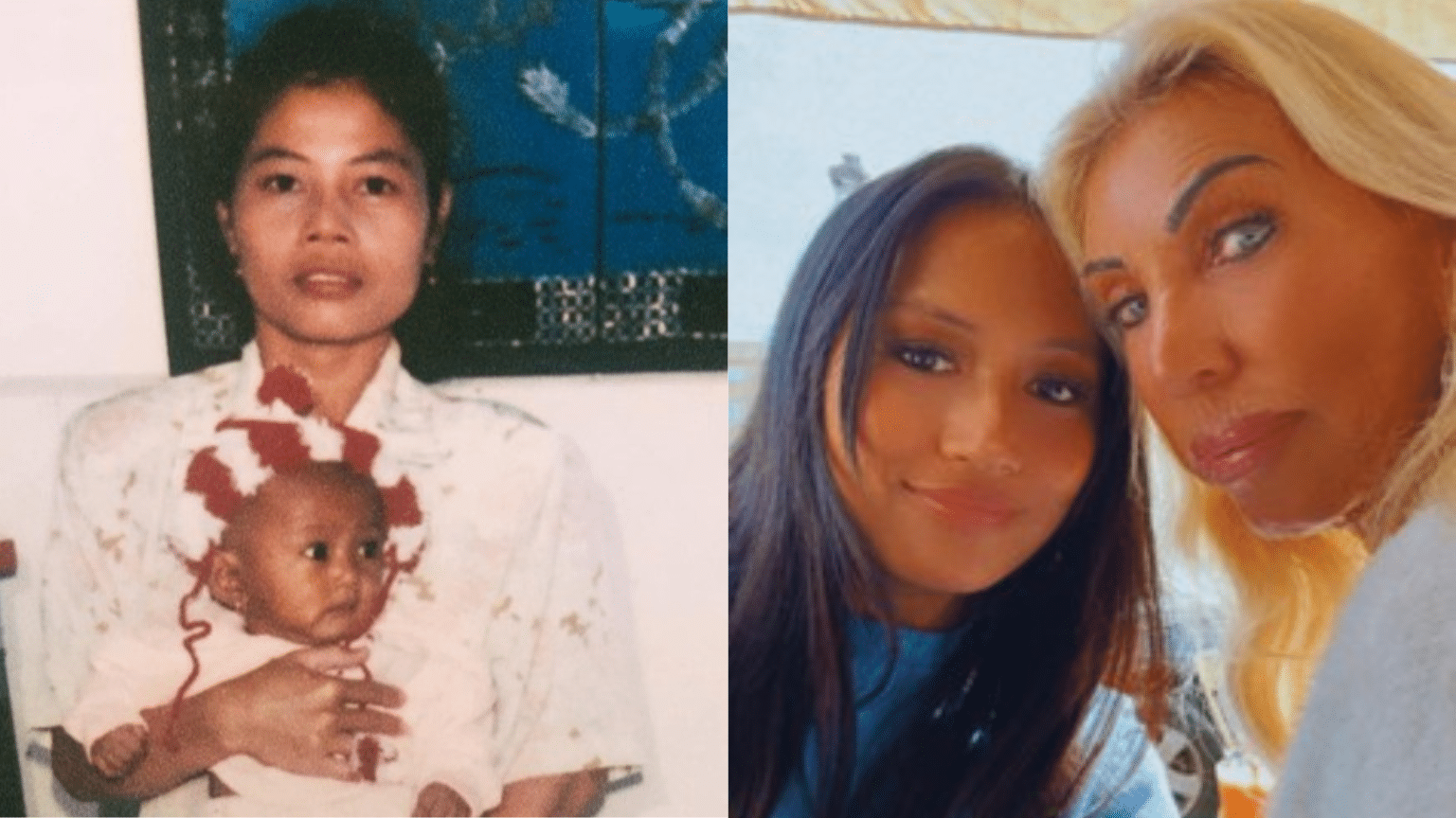

I’m the biological father of three daughters. My youngest, who’s 30 now, was diagnosed with FASD when she was 19 years old. Before then, we knew something was going on, but didn’t know what it was. She didn’t learn at the same pace as other kids, and she got involved with drugs in high school. Our extended family thought she was taking advantage of us and I was enabling her. I told them [after the diagnosis] “She has brain damage, she’s not doing this on purpose,” but they didn’t understand.

When did you realize that the services she would need weren’t available?

Her diagnosis gave us something to sink our teeth into. We thought all we had to do was go out and find the appropriate people to help her. It turned out it wasn’t that simple. Disability services wouldn’t help because of her drug addiction, addictions services wouldn’t help because of her disability, and counsellors wouldn’t help because she was “too complicated.” There’s a home share program where they take individuals with disabilities and put them into a family-type atmosphere where they live 24/7, but those homes aren’t trained in FASD. I knew they couldn’t help her.

I love and understand my daughter better than anyone, and when she lived at home, I interpreted the world for her. But I’m not always going to be here, so I wanted to make sure the world and the environment around her was as secure as possible.

What did you do?

I made it my mission to help my daughter and other people with FASD. By this time I’d met other people living with FASD and I saw how much they were struggling. Some of them were literally dying because of lack of services. Most people don’t have advocates, or are too tired, or are themselves disabled, so they can’t fight the system. I couldn’t turn my back on these people who had nobody fighting for them.

The rest of us all have a place we can go to get anything fixed—a broken bone, depression, autism—everything except FASD. There’s nothing. I decided I had to learn the system and do better at it than the government does. I’d go to the heart of things, tear the system apart, fight on the front line, and get my daughter what she needed.

I sent emails and made phone calls every day, and tracked and recorded every single discussion. I collected information through the Freedom of Information Act that I couldn’t access otherwise. I discovered that the government doesn’t follow its own policies because it doesn’t have to. No one holds it accountable.

I contacted the Minister of Health, my MLA, and the NDP critic at the time. Anyone I thought might be able to help. I’d show up at their offices every day. I threatened to sue at one point. I phoned the Minister of Health and said, “These individuals are dying. You have to change the system.” I just kept knocking at it.

There were times I could hardly function because of the toll it took to do this advocacy work while also helping my daughter navigate the world. I met Audrey Salahub of the Asante Centre, and she mentored me. Eventually people realized I wasn’t going away. After about three years, they started to see me as a as a resource rather than a nuisance. They admitted they didn’t understand FASD and asked me for help. Suddenly, I found myself at the head of a table full of government leaders, running meetings.

What was involved in getting the supportive housing project up and running?

I knew three girls, including my daughter, who were all in the same boat in terms of living with FASD and addictions. The girls liked knowing that they were all similar to each other. In this world, they don’t meet many people like them, but they hate being alone. So I said, “Listen, let’s put them in a house together [with support staff] and learn from them [what they need].” I knew it could either be very explosive or, under the right constraints, very good.

The project stakeholders were BC Housing, Community Living British Columbia (CLBC), the Ministry of Social Development and Innovation (MSDSI), and Fraser Health. I asked for things in stages instead of all at once, because that made it more likely that I’d end up where I wanted to be. CLBC provides 24/7 support staff. MSDSI redirects the Persons With Disabilities (PWD) funding to the costs of housing.

Today there are two women in the home [the third young woman tragically passed away in November]. It’s staffed by the John Howard Society, and there’s a great working relationship between the clients, their parents and family, and John Howard. We talk almost daily about what to do, how best to deal with certain situations or behaviours, etc. The staff is very willing to learn, which is rare in service providers. My daughter’s playing on a baseball team now, and she’s able to spend time with her 9-year-old son. Fraser Health is also providing a concurrent therapist, and is funding training for its existing staff, which is being provided by Tina Antrobus, one of BC’s foremost FASD experts.

What advice do you have for parents of youth and adults with FASD?

The way I approach people with FASD is that they’re the expert on themselves. We’ve got to stop trying to fix them and just ask them what’s going on. They aren’t stupid. They can talk. The phrase I hear the most from people with FASD is “Nobody understands me.” Get to know them, care for them, comfort them, make them feel safe, and they’ll open up. In my experience, when you do that, they’ll start to give you the keys to their life. They’re waiting for someone to say “I understand you and it’s OK to be this way.” Don’t try to change the person. There’s nothing wrong. They were born with weaknesses and strengths, just like all of us. The goal is to train the people around the client to create a big pillow of support.

When my daughter was first diagnosed, I thought, “Why me?” But I’ve learned some of the best lessons I’ve ever learned in my life, such as how to live in the moment, in the present. [In many ways] it’s a wonderful disability: people with FASD are incredibly giving, loving, and forgiving, and they have a high BS meter. They deserve the same chances as everyone. Sometimes I wonder if they’ve got the disability, or if we [neurotypical people] do.

Learn more about navigating FASD in the home with our webinar, FASD: Becoming the sensory detective at home. Watch it on-demand!