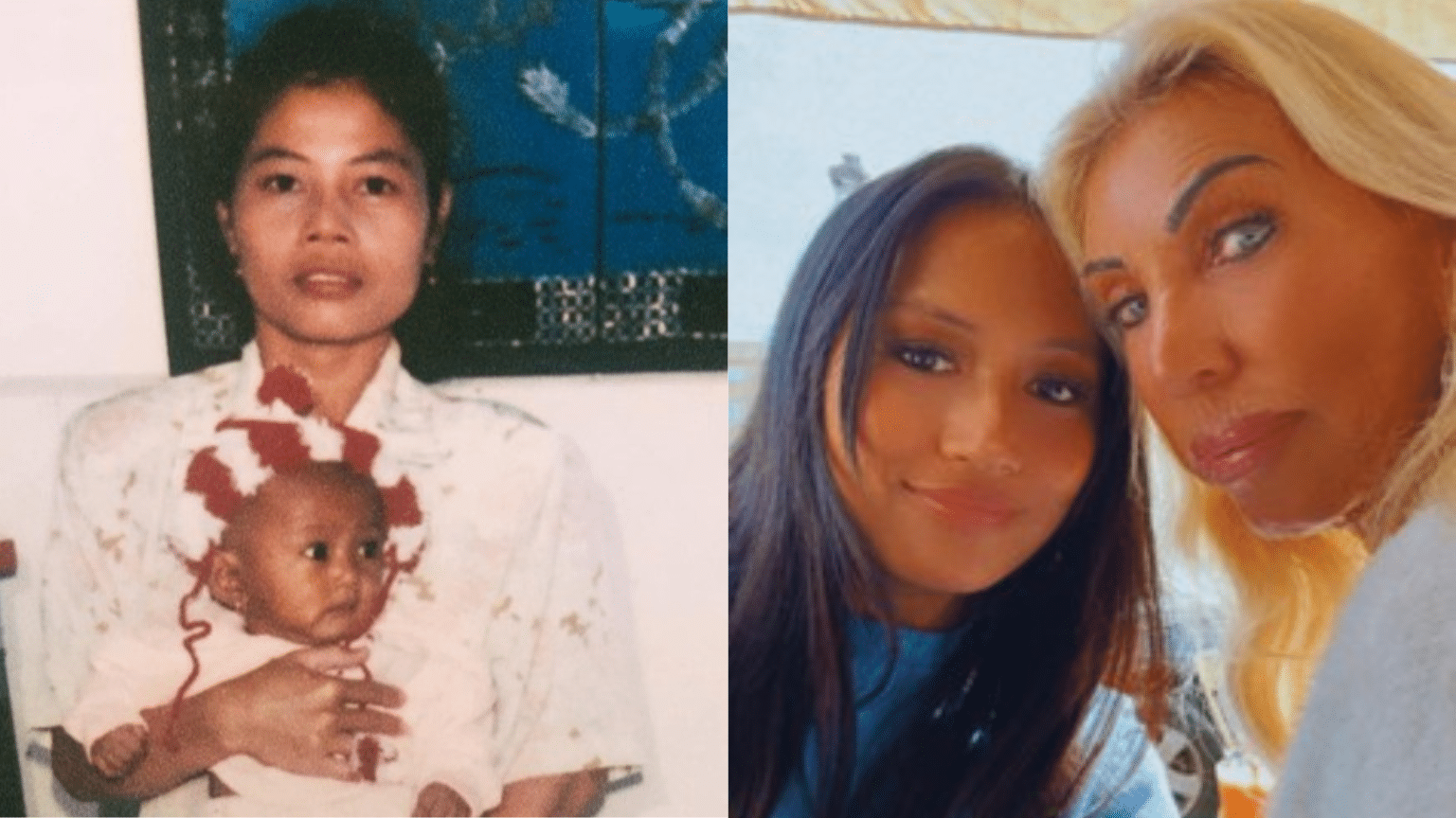

My daughter Libby was born as I held her birth mother Carla’s hand, breathing with her through the agony of labour. When her daughter drew her first breath, Carla looked at me and said, “Congratulations on your new baby.” Then she asked me to cut the umbilical cord.

I was overwhelmed by a staggering mix of joy and anguish. This woman carried life inside her body for nine months and endured gruelling pain only to give her baby to me. She seemed miraculous, superhuman. How could my husband Tom and I ever show the depths of our gratitude to her? All of my insecurity floated to the surface, and with it, a sense of dread. What if she decided to keep the baby after all? I could hardly blame her. Surely she didn’t go through all that pain just so my family could grow.

Carla broke through my mental chatter. “Go see your baby,” she said, “And pass me my cell phone.” I walked around the hospital curtain and there she was, a beautiful, perfect little human being. She took a big breath and stretched. The pure love and connection I felt is, to this day, indescribable.

Navigating troubled waters without a map

Libby’s birth parents, Carla and Eric, were in their late teens when they approached us about adopting their daughter only five weeks before she was born. Ours was to be an Aboriginal custom adoption, and it didn’t come with any hard or fast rules about openness. The Aboriginal Custom Adoption Recognition Act gives the child’s adoptive parents the power and responsibility to make decisions about openness with birth family until the child old enough to make their own decisions.

We asked Carla and Eric how they felt about openness, baby names, and their hopes for the baby’s future, but their replies seemed detached and unemotional. “We don’t really care, it’s your baby,” they’d repeat.

That’s why I was so surprised when I arrived at the hospital the morning after Libby’s birth. Carla and Eric were sleeping in the hospital bed, with Libby wedged between them. My heart lurched at the sight of this clear bonding moment, and I began to question myself. Viscerally, Libby already felt like she was mine, as much a part of me as my biological daughter, Ashlyn. I’d even been taking domperidone and using a breast pump in the hopes I’d be able to breastfeed her. But was she really my child? Were Carla and Eric planning to take her home? Did I have a right to visit her, or should I stay away until she was discharged from the hospital? How on earth was I supposed to navigate this?

I knew what I had to do: I sat down with Carla and Eric, and told them Tom and I wouldn’t blame them or be angry if they decided not to go through with the adoption. We’d be sad, of course, because we already loved Libby so much, but our hearts would heal.

Carla’s firm response was that she and Eric loved Libby, but they couldn’t keep her and didn’t want to. I should have felt relieved; instead, I felt sick.

Later that day our little family and Carla’s (who were elated about the adoption) gathered in the hospital room. Ashlyn, in her new “I’m a Big Sister” t-shirt, held Libby and cuddled with Carla. For a moment, everything seemed as if it was going to be okay.

We brought Libby home the next morning, and that evening, Eric and Carla came over for their first visit. We took photos, bathed Libby together, and took turns feeding her. It almost felt like we were one big family. We were able to talk openly about their decision, and they insisted they still wanted the adoption. Maybe it wouldn’t look like any other family’s open adoption, I thought to myself, but we’d find our own way of making things work.

The nature of addiction and trauma

Over the next ten days Carla and Eric visited daily, sometimes twice a day, and they began asking for alone visits with Libby. Carla texted me often, flip-flopping between saying things like “I wish you could have been my mother too,” and “I love you so much, thank you for giving Libby the family I hoped for,” and excruciating descriptions of the heartbreak and anguish she felt over giving Libby to us.

Carla began to confide in Tom and I about Eric’s violent abuse. We also learned about her heartbreaking battle with alcohol and drugs, and had to come to terms with the potential implications of Libby’s in-utero exposure to substances.

I wanted Carla to get support for her emotional turmoil, but she wouldn’t follow through. Our lack of boundaries, combined with Eric and Carla’s substance abuse, physical abuse, and trauma, were quickly becoming overwhelming. Tom and I wanted to honour the bond between mother and child in a loving and healthy way, but we couldn’t bond fully with Libby while also carrying so much of her birth mother’s grief and pain.

In our Aboriginal culture, a child’s adoptive and birth families traditionally give each other quite a bit of space to bond and heal, especially in the first year. In our small fly-in community, though, there seemed to be no easy way to make that happen. I couldn’t go anywhere, not even the grocery store without strangers who obviously knew Carla and Eric coming up to coo and kiss Libby and talk about how much she looked like Carla. Once, when I was picking Ashlyn up from the daycare down the hill. I was swarmed by twenty grade 11 and 12 students, including Eric, who demanded that I let them hold “Carla’s baby” and even went so far as to take Libby’s car seat carrier out of my hands.

Alienation in a shrinking world

As the weeks went by, my beloved little community started to close in on me. Eric’s parents threatened that if we didn’t let them have Libby every weekend, they’d make sure the adoption paperwork was shredded (Eric’s mom worked at the courthouse). Even worse, Carla and Eric started to barrage us with drunken texts that threatened our safety, attacked our appearance and character, and reminded us in unthinkable language that Libby would never be our “real” child.

I felt like I couldn’t leave my home for fear that this child would somehow be taken from us, and developed intense anxiety and panic that would later be diagnosed as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). How did our beautiful adoption story turn into this ugly mess?

Tom and I knew there was no way we could raise Libby if her birth family truly wanted her with them. We also knew we weren’t prepared to be part-time parents or to participate in some kind of confusing shared custody arrangement. We shared this with Carla, Eric, and their parents, only to be told, once again, “No. She’s yours.” But the threats, aggression, and unpredictability continued.

We sought counsel from elders and from Carla’s family, who strongly advised us to enforce clear, firm boundaries: no texting, Facebook, or visits for at least the next two months. We followed their advice, but I felt horribly guilty. I saw beyond Carla’s threats and hurtful texts and knew she was a hurt and grieving young woman. I just couldn’t seem to find a way to help her. How could I possibly have helped Carla heal her heart when she didn’t understand it herself through the distorted lens of alcohol abuse?

Time passes, but grief remains

It’s now been four and a half years since Libby came into the world. She’s recently been diagnosed with FASD and extreme hyperactivity. I’m still reeling from PTSD. It’s been a wild ride of joy, pain, laughter, hope, grief and loss.

For the sake of our family’s safety and well-being, Tom and I made a painful choice: we moved with Ashlyn and Libby far away from our community. We found an adoption support group that has helped us in many ways, especially as we navigate the wilderness of Libby’s FASD diagnosis. I still ache for Libby to have a strong, healthy connection with Carla, but so far, that hasn’t been possible. I do continue to mail Libby’s photos, artwork, and updates to both her and Eric, and we stay in touch with Carla’s healthy and supportive family.

Ultimately, the question I keep coming back to is a simple one: How open is too open when it comes to adoption? How can we, as adoptive parents, hold space for the trauma of birth families while also bonding with our child? How can we set healthy boundaries around messy, unbounded matters of the heart and biology?

All I know is that throughout Libby’s birth and adoption story, there is beauty, complexity, and deep, raw love.

Do you have a question about openness? Need a friendly ear to listen and help navigate?

Contact our Family Support team. They offer free confidential support and can connect you with other adoptive families in your community.