Colleen and her husband of 17 years, Jussi, live on Vancouver Island. Colleen, a former foster parent for over 20 years, also has three grown children and three grandkids. Her oldest daughter was a neighborhood kid that came for the weekend and stayed for 28 years, according to Colleen. “We have no legal paperwork, but she’s not any less ours,” she adds.

Colleen and Jussi considered adoption for over a decade until, as empty-nesters, the couple travelled to Haiti and worked in an orphanage. “That cemented the deal,” says Colleen. They began the adoption process with a specific young girl in mind, holding out hope that the adoption would be finalized, even after the post-earthquake moratorium on Haitian adoptions. Eventually, the girl’s biological father came forward and asked for her back. “We were happy for her, but it was a huge loss,” says Colleen.

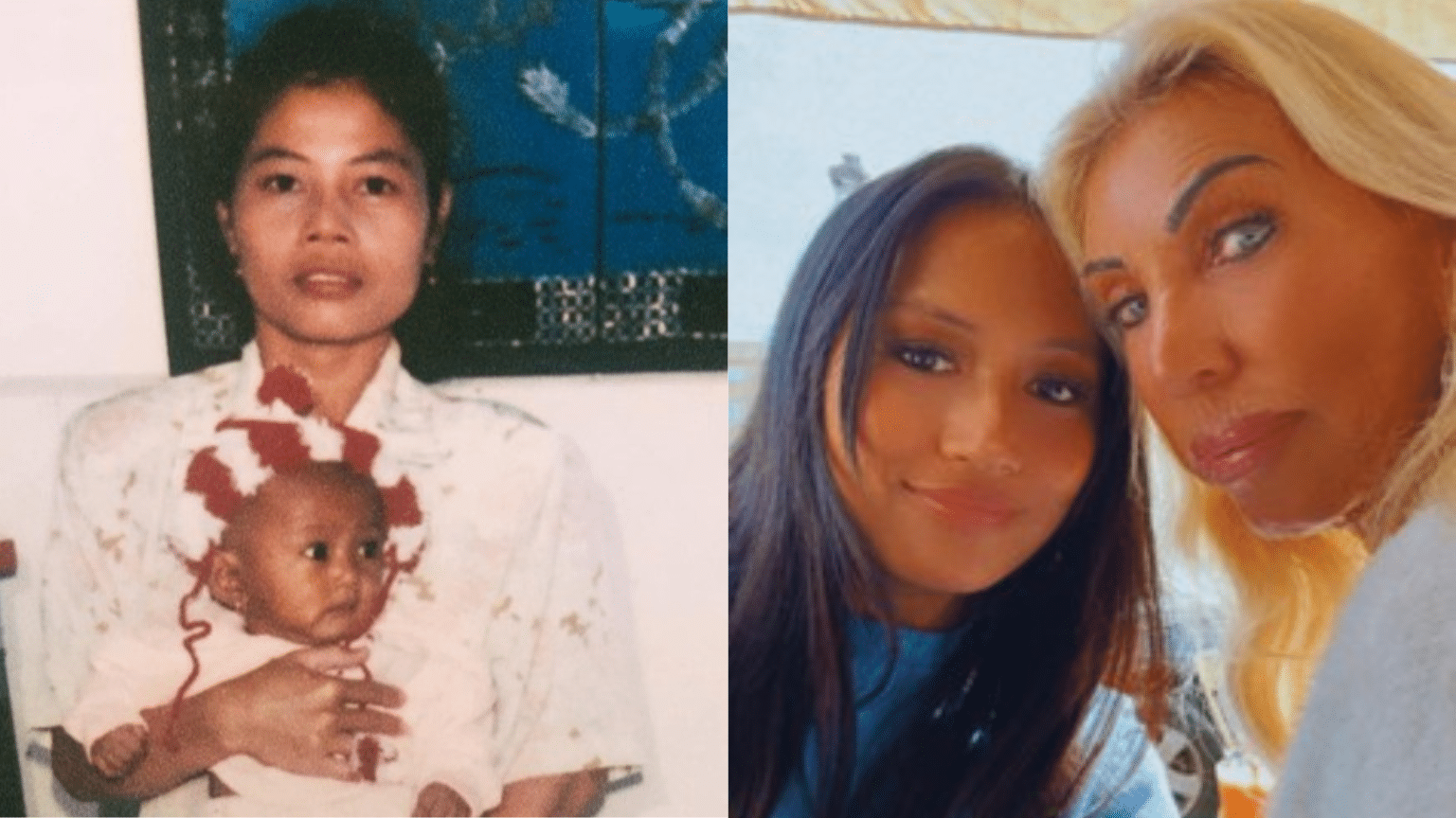

When their Haitian adoption fell through, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) was the natural next step. When they started the process in September of 2010, a new adoption program was budding there. The Yrjanas were one of the first five families in BC to pursue adoption from the DRC. A year later, they received a referral for two biological sisters. Nine months later they travelled to the DRC for three weeks and brought home the six and three-year-old girls, “Miss G” and “Miss P.” Colleen and Jussi chose to keep all of each girl’s names, incorporating their last names as middle names and adding their own family name as well.

Although the entire process was complex, expensive, and fraught with challenges, the waiting, says Colleen, was the hardest part – for them and for their girls. The sisters had been shown pictures of their adoptive parents months before their travel date, and spent every day from that point on expecting them to arrive. “That’s a long time for a six-year-old,” says Colleen. “It was really hard on them and traumatizing. ‘Why did it take you so long? I waited and waited but you were never coming,’ they told me [after we arrived]. In hindsight, for them, it was heartbreaking to wait. If I had to do it again, I wouldn’t send anything.”

The waiting period wasn’t any easier for Colleen and Jussi. “That absolute ache, that you have in that waiting period, I don’t think anyone can tell you what to expect. The child is legally yours, you’re waiting for those last few pieces of paper, and it’s just dragging on.” How did they cope? “I think we repressed it. You’re fundraising; everybody you meet tells you how wonderful it’s going to be; and you put on the face of the happy anticipatory adoptive parent. Behind closed doors you’re broken, weeping; it was very, very hard for us. They were our morning sun. I cried at the drop of a hat. Coming home, even with all the trauma, was still easier than one day of waiting. It’s an emotional roller coaster that takes you upside down, inside out, and then hangs you in the air.”

Walking to the Congo

To deal with the all-consuming wait, Colleen decided she needed something concrete to do each day. She came up with a unique idea: she and Jussi would walk the 13,808 kilometers to the Congo “in our hearts.” To cover the distance in eight months, she recruited friends, family, blog readers and members of the adoption community to walk every day and keep track of their distance.

The story of “walking to Kinshasa in our hearts” is chronicled in a children’s book Colleen wrote, called Carry Me to Kinshasa. The book, illustrated by Kelly Ulrich, tells the family’s adoption story: the long wait, their travel to Kinshasa, their first meeting, and adjusting to life as a new family. The book explicitly describes and validates the difficult emotions the children and parents experience, and emphasizes the adoptive parents’ unconditional love and commitment to their children.

“Some days when you were sad, we held you and sat for hours playing and reading. It was okay to be sad; we would always be there for you. We would love you and comfort you. That is what families do. They carry one another forever, through the sad and rainy days, through the warm and joyful days, and into new days,” reads one of the book’s final pages.

The honeymoon is over

Once the long wait was finally over, attachment – the thing Colleen and Jussi had expected to struggle with the most – wasn’t difficult. “We never expected love, attachment and commitment would be that easy. They hugged, kissed, and were physically affectionate right from the get-go. The girls had formed attachments with their first family and with caregivers at the orphanage; prior experience of healthy attachment is often thought to help adopted children attach to their adoptive family. “Our family and their first family had similarities, which also helped with attachment and bonding,” notes Colleen. They maintain contact with the girls’ first family in the Congo, sending photographs and updates through their adoption agency.

Not everything was so easy. Colleen and Jussi’s unconditional love and commitment to their new children was tested almost immediately. In addition to her many years of experience as a foster parent, Colleen works with high risk kids, and kids with autism, and is a braille transcriber. Even with her experience and skill set, those first few months were exhausting, and incredibly challenging.

“We never had a honeymoon period. Logistically, we were a family in crisis from the day we met our daughters. I knew a ton of behaviour strategies, and nothing was working. We were thankful for those in the adoption world, that we could contact and ask for help, and it was immediate,” she says.

“Because of trauma, we’ve had to be intentional parents. Everything we do is intentional or proactive or guarded. A joke in my house was ‘I’m going to try to have a shower’ because most days that was setting my sights too high. It felt like every second of the day, I was parenting (although they were both good sleepers). We were dealing with physical aggression. I couldn’t leave for a break, because even if I was just out of sight, they were terrified of abandonment. I’d read everything, I’d watched every video, I’d written a gazillion blogs, but nothing prepares you to just be in the shoes. People would tell me ‘Don’t worry, it will get better,’ and I just wanted to scream into the telephone, ‘Do you have any idea what my day looks like?’”

Because they adopted internationally, formal post-adoption support services were very limited. “We paid out of pocket for adoption counsellors, medications, specialist appointments – most wasn’t covered, even though both of us had extended health benefits. Hopefully this is an area that will change for international adoptive families. There is definitely room for improvement for post-adoption support at a provincial level.”

Colleen sought out support online, finding encouragement and listening ears on a Facebook group for families parenting children from trauma and meeting regularly with other families on theIsland and the Lower Mainland who had adoptedchildren from the DRC.

“There were days when we didn’t think we were going to make it, and days when we thought how far we had come; but most days we were just thankful for language and time. It was part of the journey and something that grew us as a family. Would we do it again? Absolutely.”

The high point in the family’s adoption journey, according to Colleen, was when Miss G asked if they could hold a dedication ceremony where everyone in the family “married” each other. “The girls wore white, boys wore suits, and everyone exchanged rings. The pastor asked the girls if they wanted to be part of our family and they both said ‘I do.’ Miss G planned the outfits and guest list, we had big party – it was what she needed to feel secure.”

Celebrities for adoption

In their small town, they quickly became what Colleen calls “celebrities for adoption.” The nosy and sometimes outright offensive questions she fields in the grocery store line bother her sometimes. “I tell my kids, ‘That person asked a personal question, and you didn’t have to answer it.’ Respect and personal boundaries continue to be an issue they encounter often within the community.” The upside of their visibility is that it’s been easy to form connections with supportive people, including community members with African heritage, whom she wouldn’t have otherwise met. “I’ve been complimented on how I care for their hair, I’ve had people give me their phone numbers. It’s been great.”

Now, less than a year after bringing their daughters home, Colleen enthusiastically encourages older child international adoption.

“The fact is that they were waiting. That’s a huge thing. Working in an orphanage in Haiti and watching the sibling groups and almost every child over five – they’re waiting. They’re waiting for their family because most families want babies. There are over 5 million orphans in the Democratic Republic of Congo. That’s the entire population of a country like Finland. It’s a country where there’s a huge need for people to adopt older children. I also use the finance thing to encourage families to adopt older children. You get a five- or six-year-old, they go to school right away, and you can go back to work!”

Colleen also speaks positively about adopting as an older parent (she turned 50 during the adoption process). “People spend way too much time struggling alone. In my 20s or 30s I would have told everyone I had it all together. The beauty of parenting in my 50s is I’m really OK to say I don’t have it happening. Help. That’s been a real blessing – not trying to be perfect.”

Colleen chose to share her family’s story because she wants to encourage parents to share their challenges and help each other. “Many people do not share their hardships because they second guess their skills or their commitment,” she says. “Let’s band together as parents and support one another. I want people to know there are great stories involving older children. Was it hard? Yes, but let’s not fluff over it and say it never happened. This story is being shared because others have walked this road and harder roads. We, as a group, need to recognize that as complex as it is, it is a gift each day to discover the unique talents and gifts of a child, to learn about their history from them and celebrate all their firsts.”

Although the matching process in international adoptions often seems like “luck of the draw,” Colleen told me that she knows at least two other families turned down her girls’ referral before they were matched with her and Jussi. “I believe we were meant to be,” she says. It’s tough to argue with that – after all, they walked 13,808 kilometers to prove it.

Carry Me to Kinshasa: our adoption journey by Colleen Yrjana and illustrated by Kelly Ulrich, is available in print and eBook editions (Colleen’s kids love to read “their” book on the iPad!) from www.friesenpress.com.