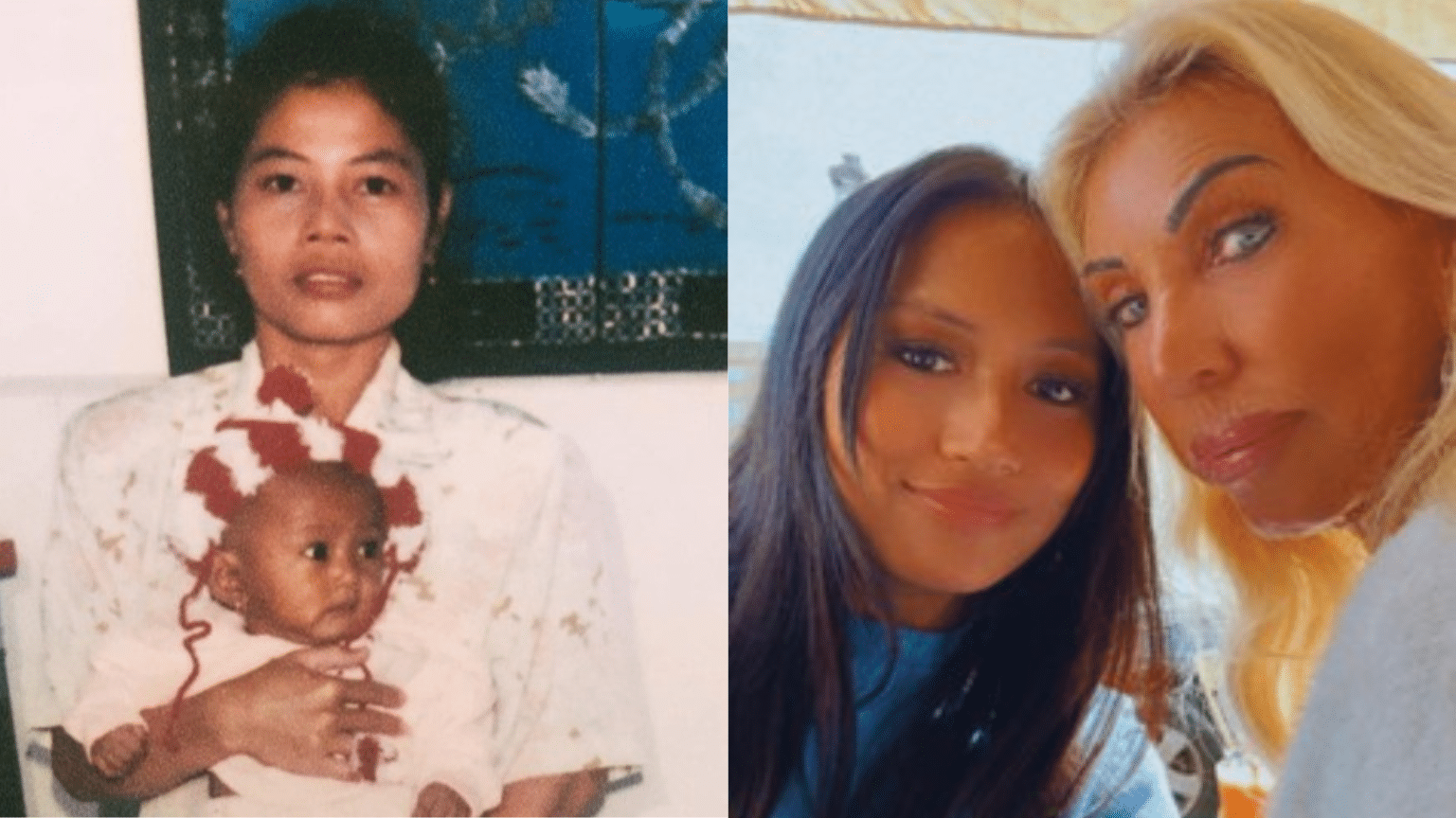

Daraly was born in Cambodia, raised in Belgium by Dutch parents, and is now spending time in Canada. She shares her adoption story openly, speaking about both the challenges and the gifts along the way. For Daraly, it’s important that adoptees are seen and heard. She believes adoption shouldn’t be a taboo subject and hopes that by sharing her story, more people will feel encouraged to join the conversation.

Tell us a little about your story

I was adopted as a baby and grew up in Belgium. My parents were always open about my adoption and tried their best to help me connect with Cambodia through documentaries, books, articles, and movies. They did the same for my sister, who is from Sri Lanka. And even though I never call them my adoptive family, because they are simply my family, there was always a quiet question growing inside me: Who am I beyond this life I was given?

As a child, I didn’t see myself reflected in the people around me. Instead, I felt drawn to anyone who looked different in Belgium: people with darker skin, different eyes, unfamiliar languages. Because my sister is Sri Lankan, I started to believe maybe I was part Sri Lankan too. At Chinese restaurants, I imagined I was part Chinese. When I saw people from Black or Latin communities, I felt a pull toward them too. It wasn’t just curiosity; it was something deeper. I was searching for where I belonged.

There was even a time I believed I might be white, or Caucasian as the term goes, because that was the world I lived in. I grew up in a Dutch-speaking, white-majority country. Most of the people around me looked nothing like me, but they shaped how I thought about myself. It wasn’t wrong, it was just incomplete.

I met other adoptees along the way, and some were willing to talk about their stories. Others weren’t. Sometimes when I opened up, people responded positively, with care and interest. Other times, I was ignored, or the conversation would shift like it was uncomfortable. I never blamed anyone for that. But I did learn that being an adoptee can feel very lonely, even when you’re surrounded by love.

As I got older, I felt a stronger need to reconnect with Cambodia. But where I lived, there were no Cambodian restaurants, no local community, no spaces to belong to that part of me. That connection was hard to make, and even harder to hold onto. Still, the pull has never gone away.

I’ve come to understand that identity isn’t always something you’re given; sometimes it’s something you build piece by piece. I no longer try to force myself into one box. I celebrate every part of who I am: Cambodian by birth, Belgian by upbringing, shaped by the people I’ve loved and learned from along the way. Whether it’s Cambodian, Sri Lankan, Chinese, Latin, Black, or Dutch, I believe all cultures should be celebrated, respected, and heard.

It’s taken me time to get here. I’m still learning, still searching, still growing. But I know now that belonging isn’t about fitting in, it’s about being seen — and seeing others too.

I’ve always stayed in touch with a few other people who, like me, were adopted from Cambodia or Sri Lanka, or somewhere else. Some of us knew each other as children, and over time we’ve reconnected in different ways. Many are on their own journeys, searching for family, for honest answers, or simply trying to understand where they come from.

Because I’ve always been open about my own story, I’ve had the chance to meet others too — adoptees from the Netherlands, other countries, both younger and older. These connections have become deeply meaningful. Even though our paths are different, sharing our stories reminds us that we’re not alone, and sometimes that means more than we realize.

What has been one of the most challenging parts of being adopted?

My adoptive parents chose me and loved me as their own, and I’m deeply grateful for that. Still, growing up, I often felt a quiet pressure — not from them, but from within myself — to always do my absolute best. It was as if I had to earn the life I’d been given. I remember thinking: “If I’m not smart enough, kind enough, good enough … maybe someone else deserved this chance more.”

After COVID, I returned to Cambodia for three months, hoping to feel closer to my roots. But even there, I felt like an outsider. I didn’t speak the language. I didn’t fully understand the customs. I was both Cambodian and not Cambodian at the same time.

It feels like being caught between two worlds, trying to balance where you come from with where you were raised. I try to remind myself that I was given a second chance, but that doesn’t erase the quiet struggle of always trying to prove I’m worthy of it.

Many adoptive families don’t mean for it to feel that way. They love and care deeply. But for an adopted child, the feeling of having to prove your worth can live quietly beneath the surface. We were given away, or lost, before we could even understand what that meant. And so, growing up, there’s sometimes a fear: “Will I be left again if I’m not enough?”

Being adopted means carrying a deep complexity (love and loss, gratitude and grief, belonging and disconnection) all at once. It isn’t something that can be solved quickly, but speaking about it honestly is a place to start.

What do you feel is most important for people to understand about transracial or international adoption?

Interracial adoption, in particular, can be beautiful, but it requires effort, humility, and awareness. It’s not just about bringing a child into your home; it’s about bringing their culture, history, and identity, and holding space for that, even when it’s uncomfortable. If I had grown up with more access to a Cambodian community, that might have helped me feel less alone in who I was.

There’s also the issue of adoption records, which is rarely talked about openly. Too many adoptees, including myself, are left with missing or false information. It makes it incredibly hard to search for your biological family or even understand where you came from. Every child deserves honesty and answers.

What’s hard is that adoption is often treated as a one-sided story: the family adopts, the child is raised, and that’s supposed to be the happy ending. But the truth is more complex. Adoption comes with a price, even when love is present. For some, that price is confusion, grief, silence, or loss of identity. For others, it’s trauma, especially when the upbringing wasn’t safe or loving.

Not all adoptees are the same. Some feel deeply connected and at peace. Others feel lost, or angry, or disconnected from both cultures. Some, like me, respect everything and everyone involved, but still carry a quiet struggle inside.

This isn’t just about adoption. These feelings can happen in any family. But with adoption, especially interracial and international adoption, the layers run deeper. Governments, adoption agencies, and families need to truly reflect on what this all means, beyond paperwork, beyond waiting lists, beyond being seen as “good enough” parents.

At the heart of it all, it’s not just about giving a child a home. It’s about giving them space to be who they are, to ask hard questions, and to not feel guilty for doing so.

Why should people have to wait years, sometimes nearly a decade to adopt a child, while others are left behind in institutions or systems that don’t serve them? I understand that protocols are necessary. It’s important to make sure a child is going to a safe, loving home. But we have to ask: who decides what makes someone “worthy” of being a parent?

Is it a perfect couple, straight and wealthy, with a spotless background? Or is it someone who genuinely cares, who has the capacity to love and support a child, even if they aren’t rich or “flawless”? People shouldn’t be rejected just because they’ve made mistakes in their past. We all have made mistake, even the people deciding who gets to adopt.

What’s often overlooked in this process is the biological families. Why are there no proper checks for them? Why are so many stories hidden? They deserve support and attention too. If children are being placed for adoption, we should at least be told who they are, what their lives were like, and shown a photo. They’re not just part of our past, they’re part of who we are.

I don’t believe in closed adoption. I believe in honesty, in talking about the truth, even if it’s painful or complicated. It’s better than being left with silence or lies. Because the not knowing can hurt more than the truth ever could.

People often say, “You should be grateful.” And yes, I am. My adoptive parents were always honest with me. My mother gave me my papers when I was ready and told me I could go back to Cambodia whenever I felt the time was right. I’ll always be thankful for that.

But even with honesty, adoption still hurts. It comes with deep questions about belonging, worth, and identity.

But even with honesty, adoption still hurts. It comes with deep questions about belonging, worth, and identity. Sometimes, my mom and I go back and forth because she worries that the truth causes me pain. And she’s not wrong — it does. But it’s also all I’ve ever wanted.

And for many adoptees, it’s the same. We’re not asking for perfect stories. We’re asking for real ones, for space to feel what we feel, and for systems that respect that adoption is not just a legal process, but a lifelong journey for everyone involved.

People who haven’t been adopted may have opinions, and that’s okay. But only adoptees truly know what it feels like to grow up with these questions. And only biological families know what it means to lose a child — often under pressure, or in situations that were never fair to begin with.

Never forget the stories of the biological families. They absolutely deserve to be seen, supported, and treated with the same care and attention that adoptive families receive. Too often, they are left out of the conversation, judged, ignored, or erased entirely. But their stories matter too. Many of them made impossible choices, often under pressure, in silence, or without real guidance. They need love, support, and compassion, not shame. Adoption is not just about gaining a family; it’s also about acknowledging the loss of another. Both sides deserve to be heard.

That’s why adoption must be about more than forms, money, or appearances. It must be rooted in truth, care, and humanity.

Have your feelings about adoption changed as you’ve gotten older?

Yes, adoption is complicated and sometimes even controversial. I know there are people who are against international adoption and believe that children should stay in their birth countries. I understand that view more now than I did growing up.

When I was younger, being adopted felt like the most normal thing. I loved my family, and I still do. I was told I was “lucky” or “privileged,” and for a long time I believed that too, or at least felt like I had to. But as I’ve grown older, I’ve realized that love and gratitude can coexist with pain and questions. I don’t need to keep proving my love for my adoptive family to be allowed to share the other parts of my experience.

What’s one piece of advice you would share with another adoptee?

Don’t think you’re not worth it.

Many adoptees, myself included, have moments when we wonder if we were ever truly worthy of a life with our birth families. But the truth is, we are. Every adoptee is worth love, care, and belonging, no matter where they come from or what their story is.

If you’re adopted, please know that your feelings are valid — the confusion, gratitude, grief, love, and questions. You don’t need to hide them or apologize for them. You are allowed to feel all of it.

And if you’re adopting, especially across cultures, understand that your child will one day have questions. They’ll want to talk about the hard parts. Give them room for that. Let them ask, and give them honest answers, even if they’re difficult.

Because at the end of the day, every child, adopted or not, deserves to be loved, seen, and listened to. Life will always have good and bad moments. But what matters is that children grow up knowing they matter, not for what they give or how grateful they are, but simply because they are here.

Is there anything else about your journey or perspective that you’d like to share?

I’m still figuring myself out.

Adoption is a big part of my story, not all of it, but a part that shapes how I see the world and myself. It comes with struggles, but also with chances I might not have had otherwise. I carry both.

I don’t claim to be the best example of an adoptee. I’m just a human being trying to understand my place in the world, like everyone else. But I know one thing for sure: we need to talk about adoption more openly.

For too long, many of us have kept our feelings quiet, out of fear, guilt, or just not knowing how to begin. But that silence doesn’t serve us. It doesn’t help the next generation of adoptees, or the families, biological and adoptive, trying to do their best.

Adoptees deserve to be seen in communities, in the media, in conversations that matter. Our stories aren’t all the same, but they are worth hearing. Because when we share them, we remind others they’re not alone.