Brandan’s story – and mine

As the adoptive parent of 10 children with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders, I know how difficult it can be to access services and develop a support network for people with FASDs. I regularly give presentations about FASD to groups, using the story of my son Brandan’s life (with his full permission) to illustrate these difficulties. I’ll share a condensed version of his story in this article.

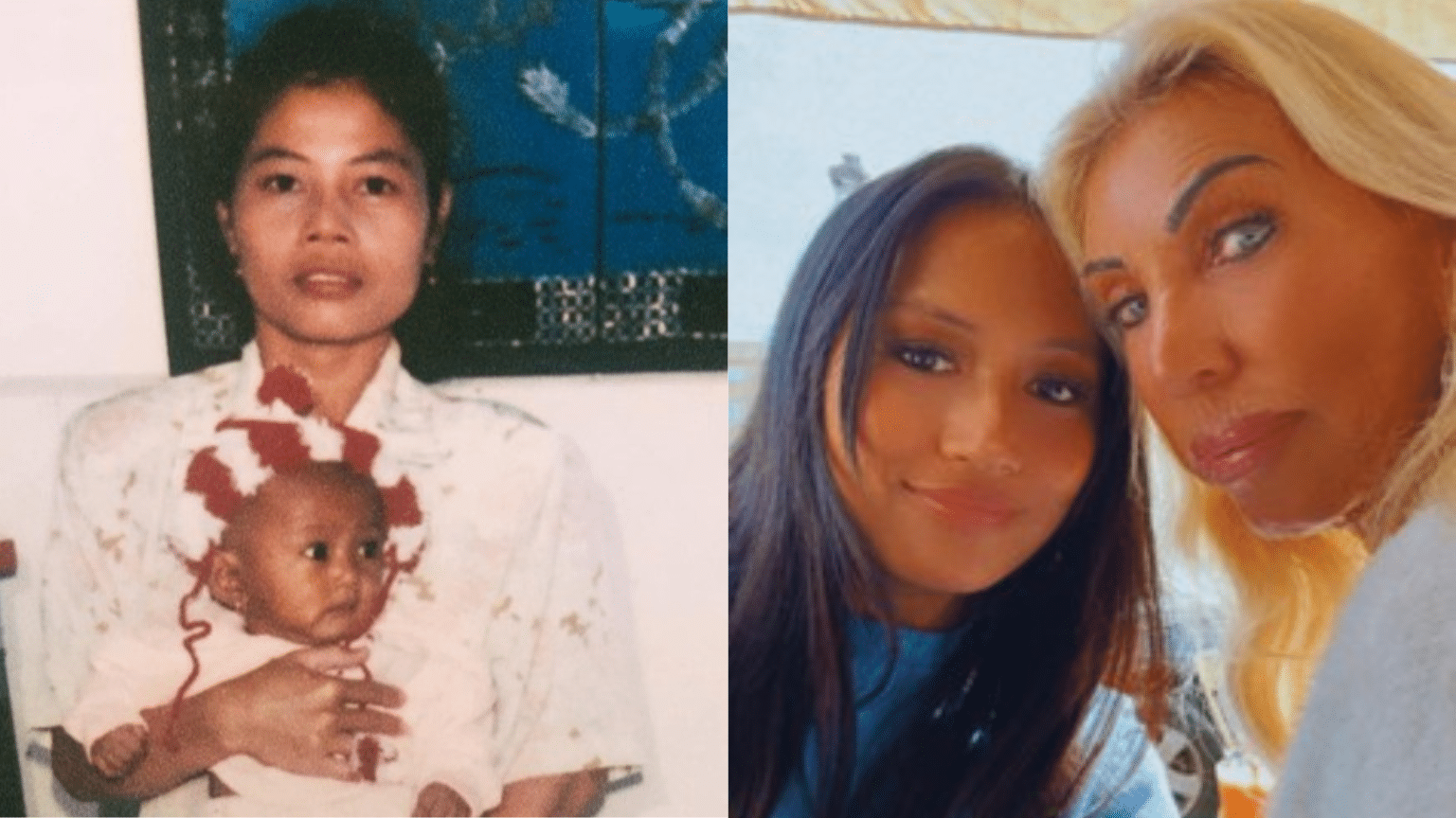

When the foster care placement desk called my husband and me in June of 1995 and asked us to take placement of an eight-day-old infant who was in the NICU at the University of Washington hospital, we were better prepared than many families for a child with special needs. I have a medical background, we had been fostering for three years, and I had already brought eight foster children to the FAS Diagnostic Clinic at the University of Washington. This new placement would require me to draw on all those skills and experiences. Baby Brandan was exposed to alcohol on a daily basis during his birth mother’s pregnancy. He was growth deficient, and was experiencing respiratory distress, seizures, and feeding problems when we brought him home two days later.

Amazing joys and profound challenges

Brandan was diagnosed with full fetal alcohol syndrome at three months of age. At that time, he was given a very poor prognosis. He only weighed 11 pounds by one year of age, he had a feeding tube for over a year, and he didn’t crawl until he was 14 months old. He walked with an orthopedic walker at 24 months old and finally walked independently at three years old. Over the years, he qualified for speech and language therapy, occupational and physical therapy, and feeding therapy. He suffered multiple respiratory, sinus, and ear infections, had many surgeries on his ears, and suffered hearing loss for a period of time. For the first three years of his life, he attended at least one specialist or therapy appointment on almost every day of the week.

Brandan qualified for special education and received services in a birth to three program, a developmental preschool, and a special education program throughout elementary school, middle school, and now in high school. His cognitive and academic challenges are very profound. He also shares his unique and amazing sense of joy with the world. He often says, “This has just been the most beautiful day.”

When Brandan was younger, he had enormous difficulty with sensory processing. He couldn’t handle being in the cafeteria at school, he couldn’t attend assemblies in the gym, and he wasn’t able to attend the graduation ceremony of one of his older brothers because of the echoing in the auditorium. Four years ago, we went to the Everett Event Center to see the Harlem Globetrotters. Brandan was so overwhelmed and overstimulated that he dropped to the floor in a fetal position and dry heaved. He continues to work with community providers and has made tremendous gains.

Elvis impressions and swimming lessons

Today, Brandan’s self-confidence and self-esteem is astonishing. He loves music, including rhythm and blues, country and western, big band swing, bluegrass, and old-time rock and roll. He has always loved singing and playing instruments. He was thrilled when he transitioned to high school and was given the opportunity to join the concert band and then to be in the percussion ensemble and drum line. He takes drumming, guitar, and banjo lessons. He even performed his Elvis impersonation at a National Conference on Fetal Alcohol Syndrome in Nashville, Tennessee in 2010 in front of over 300 attendees.

Brandan’s successes haven’t come easily. Washington State, where we live, has been at the forefront in FASD diagnosis and research for years, but we often lacked specific intervention services for affected individuals. For example, Brandan has very low muscle strength in his hands and his core. We had to be creative and persistent in order to locate swimming and guitar instructors who recognized his talents and accommodated his challenges. These were just two interventions that required extensive amounts of research and exploration.

A diagnosis of FASD may assist with securing eligibility for a program or service. In my experience, though, we often get further if we specifically discuss the affected person’s unique needs and strengths, such as math disability, low processing speed, poor working memory, social immaturity, kindness, motivation, and being musically gifted. We then go on to cultivate relationships with interested and caring people who are willing to listen and learn.

Supportive relationships make the difference

More than anything else, these kinds of supportive relationships are the key to Brandan’s success. In 2003, one of my friends and I wrote a grant proposal asking for funding to hold a three-day FASD Family Summer Camp. The proposal was successful, and the camp was a wonderfully encouraging and positive experience for our family and for 12 other families as well. Out of that camp grew a support network that eventually became the Washington State affiliate to the National Organization for Fetal Alcohol Syndrome. As the Executive Director for NOFAS Washington State, along with a powerful volunteer board of directors and passionate families, I created an online support group, a face-to-face support group for parents/caregivers/community providers, a teen social skills group, a friendship group for elementary aged youngsters, conferences, and summer camps. These programs and networks have been our family’s lifeline over the years. Unfortunately, due to state budget cuts, NOFAS Washington no longer receives any state funding.

Brandan’s support team now consists of devoted parents, encouraging siblings, a phenomenal pediatrician, the Special Olympics, drum and banjo instructors, a special education teacher who is always open to learning, a band teacher who makes sure that Brandan is able to shine and is included in all events, and a group of amazing friends at school that include cheerleaders and band members. He has been selected by his band classmates as the most inspirational student for three out of four years. This support network is truly the most important intervention and support in Brandan’s life.

Julie Gelo is the legal mother to 16 children, ages nine to 48. She and her husband were licensed foster parents for 22 years. Eleven of their children have been diagnosed with FASD. Julie has been the Family Advocate for the FASD Diagnostic Team at the University of Washington (UW) for 18 years. She is the Executive Director for the National Organization on Fetal Alcohol Syndrome Washington State. She is a Continuing Education Coordinator with the Alliance for Child Welfare Excellence at UW and presents on FASD, Sensory Processing Disorder, The Nurtured Heart Approach, and Educational Advocacy throughout the US, Canada, and Europe.

| FASD 101 Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD) are a set of lifelong neurodevelopmental disabilities. It is estimated that the incidence rates of FASD run as high as 9 to 10 cases per 1,000 live births in the U.S. Fetal alcohol syndrome disorders are the leading known cause of intellectual disability in the Western world. Many studies have found that full FAS is the most costly birth defect in the United States. FASDs are known to span the lifetime of affected individuals. Secondary disabilities in lifestyle and daily function, such as mental health/behaviour problems, trouble with the law, and independent living have been found to be both frequent and debilitating for affected individuals. Raising an individual with FASD has many rewards, as well as many dilemmas, costs, and stressors. Raising a child with FASD is often associated with feelings of guilt and shame, financial strain, frustration with the lack of knowledgeable professionals, and multiple time demands. The search for support The appropriateness of any given strategy is dependent on the needs of that child. The types and depth of services available vary greatly, depending on where the child lives. Another unique factor is that the majority of children with FASD are being raised by foster and/or adoptive families, or in relative placements. Many of these families are large and include multiple individuals with special needs. This requires high levels of structure and organization on the part of the caregiver/parent. The learning and behaviour phenotype of FASD is unique to each individual; is based on the degree and timing of prenatal alcohol exposure; and is affected by genetics, other prenatal factors, and postnatal considerations such as multiple placements, abuse and neglect, and living with chaos and dysfunction. This creates even more confusion in creating and accessing services for FASD. There are many protective factors for individuals with FASD, such as early diagnosis and intervention, and a safe, stable, nurturing home environment free from abuse, neglect, and substance addiction. It is important that our communities and resources be developing targeted interventions, reducing placement disruption, and enhancing the outcome of affected individuals. Despite all the challenges, I still believe that with individualized supports and interventions, we can improve outcomes in quality of life for children with FASD. |