Jared is a happy, active toddler.

As I visit with his parents, Jared amuses himself with various toys. When he tires of playing alone, he climbs onto a parental lap and plays “Got your nose” or tries to engage in a game of tickle or playful roughhousing. In between interacting with or checking on Jared, his parents lovingly relate their journey to parenthood. With the serendipity that is so common to adoption, just as his daddy states that “Jared was obviously meant to be our son,” the tyke lets out a loud whoop of “Yeah!” as he romps about the room.

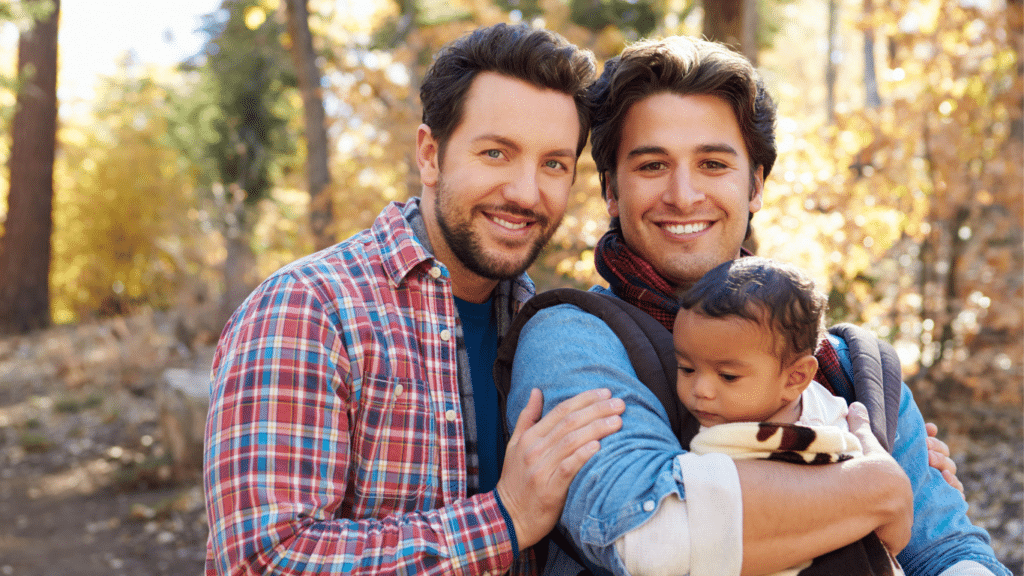

Like all adoption stories, Jared’s is magical and unique, with the added distinction that Jared has two fathers, Rob and Scott (Dad and Daddy). The couple had been together for many years when they began considering parenthood. Scott explains they “needed to wait until the legislation changed, and once same-sex parents had adoptive rights [Bill 51, 1995 Adoption Act] we went for it.” After their home study was completed, they were discouraged by the then lengthy waiting time that was involved with the Ministry. They registered with an agency, and “during an eighteen-month period, we had three local matches and two in the United States.” For Rob, “one of the biggest things in our adoption story is that three pairs of local birth parents wanted to meet us. They didn’t just say, ‘Oh, gay couple – don’t want to go there.’ For whatever reasons, the birth parents chose to meet us, over all the other people, which was quite amazing. And that’s a message that we would like to get out to other same-sex couples: local adoptions can and do happen.” Unfortunately, and for a variety of reasons, Rob and Scott’s local adoptions did not work out.

Rob recalls that later on, and in the space of one week, “we had a match in Chicago and a match here. We decided we’d go for the local one, and that fell through. Then we phoned back to Chicago, and that one fell through as well.”

For Scott, going “from two to nothing in 48 hours was a drain. I was really unprepared for how devastated I would be. I asked, ‘What did we do?; What was wrong?’” Then both Scott and Rob realized that “if it wasn’t going to happen, it wasn’t going to happen, and that is something that we eventually came to accept – that those adoptions weren’t meant to be.”

Rob emphasizes “that what is nice about the Belonging Network, is all the support we’ve received from them. When the adoptions didn’t happen, we phoned them up, and they were very good to talk to, to listen to us, and put us in contact other people who were going through the same thing. It was great having that support, along with that of our family and friends.”

Scott explains that Jared’s adoption “went the way it was supposed to go. We got the call on a Thursday and ended up in Chicago on Monday, and spent the week doing the usual paperwork and court appearances.” Jared’s adoption was “done as a single parent adoption through the state of Illinois. As a gay couple living in Illinois, you can adopt jointly; but if you live in BC you have to adopt as a single parent and then do a co-parent adoption later, which we did. We hyphenated Jared’s last name as a way of indicating that we are both his parents, and his birth certificate names both of us as his fathers.”

The only major difficulty the family encountered was due to the weather. Rob and Scott relate that their week in Chicago “was really challenging physically, given that the temperature was 95 degrees the entire time we were there. There was a huge convention in town so there wasn’t a hotel room to be had. We ended up miles and miles away from anything. We had an un-airconditioned hotel room for the first while, but we finally badgered them into giving us an air-conditioned room because we had a five-day-old baby and were flying by the seat of our pants. Jared spent that week sleeping in an open drawer, which was the safest spot for him.”

While Scott and Rob were experienced with changing diapers and mixing formula, Rob remembers “that the only time we had a really rough time, was when we were in the hotel room in Chicago, and Jared would not calm down. He was just crying and crying, so we pulled out the baby book. We’d checked everything already, but we wondered if we were missing something. We got to the part about colicky babies, and it said it would only last five to six months, and about that time I started crying. You know, it’s four in the morning and you can’t phone home because it’s midnight back here, and you’re in a hotel room with a screaming baby – what do you do? We knew it wasn’t fatal: it was 95 degrees and Jared was miserable.”

Both Rob and Scott admit that there are benefits to being “two men and a baby,” although those benefits can become embarrassing: “there was a fawning of attention on the airplanes, in the hotels, and anywhere we went because the attitude was ‘What do you guys know about babies? Guys need a lot of help.’ We got extra food, we got pillows and many other little extras. Admittedly, we did take advantage of anything extra at that point, because we were pretty frazzled after a week in a hotel room.”

“Getting home was comparatively easy: only one delayed flight and two changes of planes just to get out of Chicago.” Returning to Vancouver via Calgary did have one advantage: Rob and Scott’s families were there to meet them. Scott says, “There was a wall of people. They had rented the Board Room at the airport hotel, so we had a baby shower during our three hour layover. It was so wonderful.”

Rob took a year’s leave of absence from work and found that he had many interesting reactions to a father with an infant: “If Jared was a little fussy or wanted his bottle, people would look at me and say, ‘Oh, he wants his mom.’ I would just look at them and say, ‘You’re talking to her.’ That would usually silence them.”

People are sometimes intrusive because of the family’s racial diversity (Jared is African Heritage, Rob and Scott are caucasian). Rob and Scott find that they are often asked if Jared is adopted. When Jared was younger they “often took that opportunity to educate them,” but later “found a way around that. We would reply, ‘It’s great that you asked me this personal question. Who in your family is adopted?’ Sometimes they would say things like, ‘My child is adopted,’ or, ‘I am adopted,’ and that would be a way of connecting and talking about it. But if they just were being nosy, they wouldn’t have any answer.”

Scott notes that they also “get a lot of questions like, ‘Is your wife black?’ or ‘Is his mother black?’ There are sometimes individual reasons for their prying, but when the three of us are out it is fairly obvious Jared is adopted; and it’s fairly obvious that there isn’t a mother involved when he’s yelling, ‘Dad, Daddy, get over here.’”

Another challenge is the way other parents react to “two men who aren’t visibly matched” to their child. Rob recalls that “one day at the park, Scott was playing with Jared near the slides. I was watching as another boy began to fall off the slide, and Scott caught him. I scanned the park and sure enough a dad from far away ran to the slide to figure out what this man was doing there. Once Jared called Scott “Daddy,” there was suddenly permission to interact with the children.

Rob and Scott are “aware that there’s going to be special issues for Jared to deal with and we’re preparing ourselves by staying involved with the Belonging Network”. They also belong to two support groups: one for same-sex parents and one for transracial families. These groups allow them a wide range of friends “and a lot of support.” Rob stresses that they are “taking the opportunity, from an early age, of always talking to Jared and trying to foster and nurture a really open relationship with him so he’ll know that he can talk to us about anything.”

Reflecting on parenthood, Scott says that “in some ways it’s been a really big change and in other ways it hasn’t. I think it’s made our relationship a lot stronger since we’re both very focused on this other entity in our lives. One of the other benefits of being a father is that I can be a complete goof in public and people understand that because I’ve got a three-year-old who’s being as goofy as I am. I also find it really energizing just being around him; I feel a lot younger because I’m just out there doing stuff with him.”

Rob adds that “kids also put a lot of perspective in your life – what’s important and what isn’t. I think that’s a huge advantage to parenthood – he perspective of what’s first and foremost.” Scott agrees and emphasizes that for “an adult or a couple who may not have been given the opportunity to have children, work is often a major focus. I know it was mine for a long time: gotta go to the office, gotta get ahead. My perspective on that has shifted because there are added responsibilities now that we have Jared; I’ve really learned to take advantage of that by saying, ‘Sorry, my work day is over. My son is waiting for me.’”

According to Rob, one of the other advantages of fatherhood is that he and Scott, who have now been together for 16 years, have “started having more people over to the house, and doing the nesting thing is nice.” An added bonus is the support they have received from their bosses, co-workers, family and friends. Scott laughs that Jared is his parent’s fifth grandchild but, “for the first couple of years of Jared’s life, my mother [who lives in Calgary] wouldn’t go six weeks without seeing him. It’s been quite wonderful. Everyone in the family is very interested to see how he’s doing, how he’s growing, and how he’s just being who he is.”

Rob says that their “family doctor is very supportive as well. When I phoned his office to say our newborn needed a check-up, he had us come in at five when the office was closed. He spent two hours with us, basically on his own time, going over everything with us and checking Jared over. That was quite comforting.”

Rob’s advice to other prospective adoptive parents is that “there are always going to be better times or worse times but, if you’re thinking about it, just do it. You get that phone call and it doesn’t matter what else is happening. It was probably the worst time for our work, ever: we were both so busy, but you just have to walk away from it. Whenever I talk to any prospective adoptive parents and they’re waiting, I say, ‘Just do it. Once you have a child you’ll kick yourself that you didn’t do it sooner.’ And the message that we would like to get out to other same-sex parents is that it does happen. It’s not some bizarre one-in-a-thousand thing. Lots of same-sex adoptions are happening now. Within the last three years the Ministry has changed and it’s amazing how much support they will give you. They’re now working very fast.”

Both Scott and Rob agree that parenthood is wonderful because it gives one “the chance to totally love another person unconditionally; the chance to pass down all the valuable insights and perspectives we’ve learned from our families and relatives; and the opportunity to be a kid again and experience the world through the eyes of our child.” What makes being a father so special is “when it is only our hug or kiss that makes the hurt go away; having thoughtful discussions about why Captain Hook is mean and Santa Claus isn’t, even if they both wear red jackets; and the enormous sense of pride we feel at being called Dad and Daddy.”

As our visits ends, I notice three wooden blocks bearing the initials R-J-S. The blocks are more than a decorative device; those structures represent the unity, stamina, and commitment that are the foundation of this, and all successful families.