As adoptive parents who began our journey with our application to adopt almost 25 years ago, we’ve seen some changes along the way. One of those changes has been regarding the adoption of children of First Nations ancestry into non-First Nations homes.

Our first adoption was a child of First Nations ancestry, and we were given very little information about his birth mother’s community, or even about how to support his culture. Fast forward a few years and his half brother joined us.

For a time there was a moratorium on adoption of First Nations children into families who lacked the cultural connections needed. We fostered our second son of First Nations ancestry for several years until we were able to adopt him. The Band their mother was from sent a letter of support along with some information about the community. There was no culture plan created; this was before this process was in place and mandated. Indeed, this was before openness was practiced the way it is now, and there was essentially no easy connection or communication established between our two sons and their older siblings, cousins, and extended family.

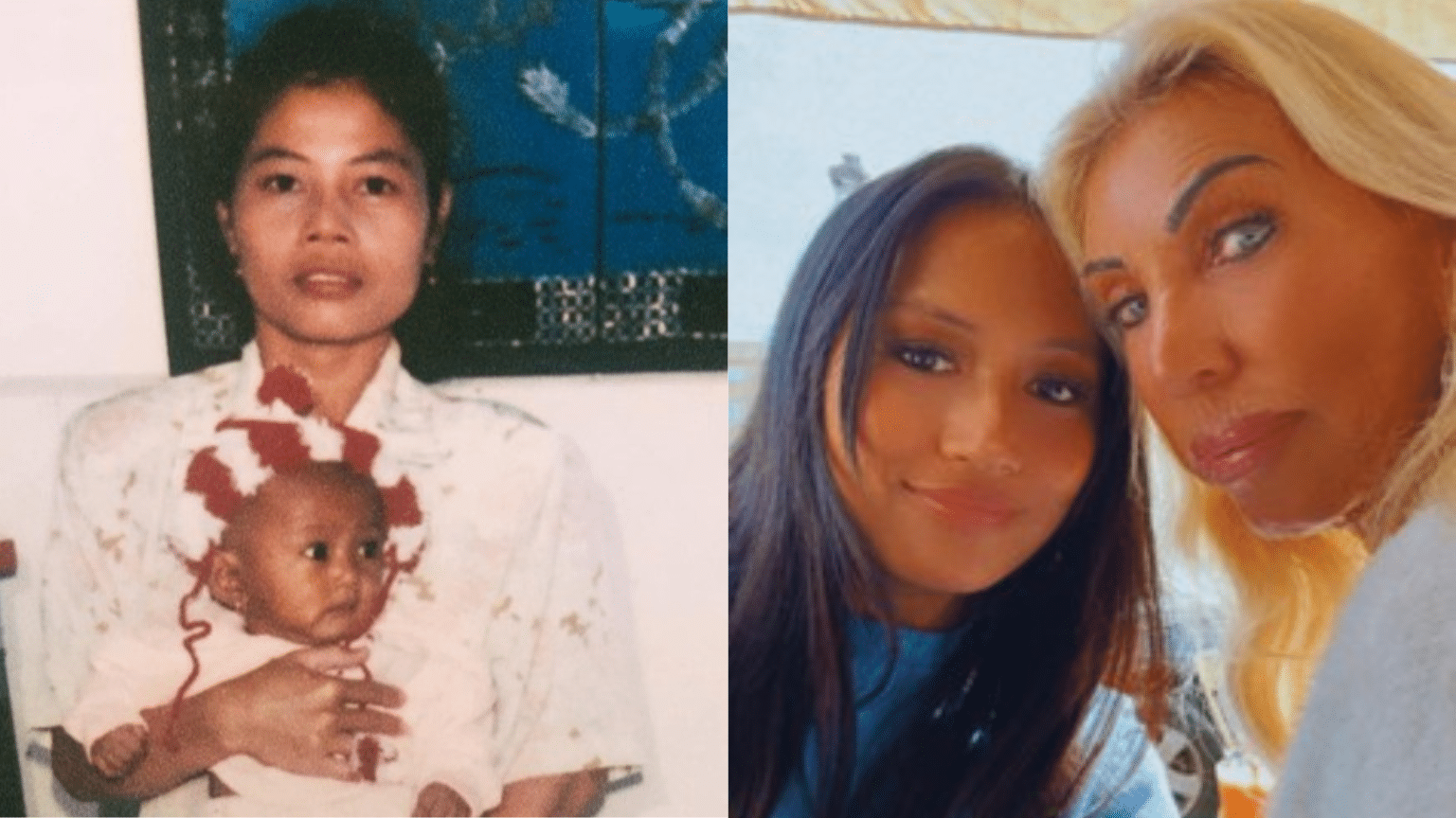

In a few years, these two boys became young men. I initiated contact with their mother’s First Nations community, which eventually resulted in a flurry of communication. The boys met with siblings and cousins. While we were willing to be part of this process, they opted to do this on their own.

They continue to have contact with their birth family members, mostly through Facebook and other online networking, and have occasional visits. They have not made the journey to their First Nations community, although I hear them talk about doing it as a family at some point. (My two sons are the youngest of their birth family).

We took advantage of a variety of opportunities to include our sons in activities and events for children of First Nations ancestry offered through a Friendship Centre, a school district, and a First Nation community. I now know that these were not enough. The activities were not specific to their traditions, and they did not have the chance to make the connections to mentors that would have been really good for them. As parents we simply did our best with what we knew, and the resources we had available.

Our sons are still well connected to us; I feel lucky that it is so. I know not all adoptive families survive the challenges of reconnecting with birth family and the accompanying journeys.

I’ve heard many painful stories, particularly from those adopted as part of the “60’s Scoop” who were sometimes placed in communities far from home, and where the culture in every way was distinct, unfamiliar, and sometimes unwelcoming.

I think we’ve come a long way. We still have a disproportionate number of children of First Nations ancestry in foster care, which is a whole other story and a challenge in itself that needs a different set of steps to remedy. There are insufficient Indigenous foster and adoptive homes for the children who need them. That’s another place for change.

But for the children who do end up being fostered or adopted by non-Indigenous families, there are processes in place to prevent the losses of the past. Things aren’t perfect and there is much to do. But it’s an improvement over the planning that took place for my sons, over two decades ago. And that’s a start.

Understanding Indigenous Adoptions

Approximately half the children currently in foster care who are waiting to be adopted are of Indigenous origin. During the 1950s and 1960s, many Indigenous children were adopted by Caucasian families. Though in some cases the adoptions were successful, in many they were not.

It is now generally accepted that Indigenous children do better when living with families that share their heritage. The BC Ministry of Children and Family Development aims to place as many Indigenous children as possible with Indigenous families. Eventually, they will move to a system where Indigenous adoptions are handled by an independant Indigenous government agency.

There are some children with Indigenous heritage who, for a variety of reasons, can be placed with non-Indigenous parents. When this happens, the child’s new family must agree to sign and commit to a “Cultural Plan,” which outlines how the family (with support from a local Indigenous Band) will build and maintain a child’s link to his or her culture and heritage.