“If I were an adoptee, I think I’d want to search for my birth parents. I’d be curious, I think,” Cathy tells me. “Oh, no, I wouldn’t want to,” says Joanne. “I was raised by my biological parents and I may look like them, but I am nothing like them in personality. Who cares whose nose or hands you have?”

It’s my opinion, as an adoptee, raised without knowledge of my biological parents, that it’s impossible to know how you would feel about searching if you didn’t grow up adopted. It’s impossible to accurately place value on knowledge that you’ve had all your life. That knowledge often comes at you sideways, through observations you make, or through offhand comments you hear growing up. It’s knowledge that gives you a sense of your history, of where you came from. It gives you roots. Do we all need a sense of our past, as well as a belief in our future, in order to live healthy lives? I don’t know. But I believe I did.

I was adopted at five days old, and I can’t remember a time when I didn’t know I was adopted. In some ways, it felt a bit like celebrity. Everyone knew I was adopted. Not that unusual, my adoptive mother discovered she was pregnant shortly after I was adopted. My brother and I were often dressed as twins. How could we be so close in age and not be twins? So while I was growing up, the story that I was adopted was told repeatedly. My parents telling me that I was special, that I had been “chosen,” contributed to that sense of celebrity. Being adopted was anything but an embarrassment: it was a badge of honour.

Curiosity about my birth mother, in particular, was always present. My mother told me that when I was six years old, I came back from a trip on the city bus reporting excitedly that I was pretty sure I’d seen my birth mother. She’d looked just like me! My mother was stunned, never having been prepared to expect any of this. She wondered what she was doing wrong that I continued to have this interest in my birth mother.

I look nothing like my adoptive family. They are shorter, have dark hair, strong features and tan easily. I am tall, have lighter hair, less pronounced features and very fair skin that burns easily. These differences didn’t stop people from saying that I looked like my mom.

This bothered me. I felt that I looked nothing like her, and such comments felt like some sort of denial of the truth of my heritage, a heritage I was not allowed to know anything about.

As I got older, I learned to answer questions from doctors with, “I don’t know, because I’m adopted.” The usual answer was, “That’s okay, it’s not important. Don’t worry about it.” These were just standard questions, right? But why did they ask if the questions weren’t important?

Apparently, I have a common face, since people repeatedly asked me at parties or bus stops whether I was related to so and so. Wondering if I might actually be related to any of these lookalikes bothered me. I wanted to know. What if I passed a sibling on the street and didn’t even know it? What if I dated one?

People would comment on the fact that I was so tall and fair. “Are you of Scandinavian background?” they’d ask. I resented not knowing even my ethnic background. Everyone else seemed to have that knowledge.

Then there was the fact, more pronounced after my father died when I was 10, that I felt out of place in my adoptive family. I’m more intellectually oriented; they’re more athletic and don’t read, to give just one example. I resolved to find my birth mother.

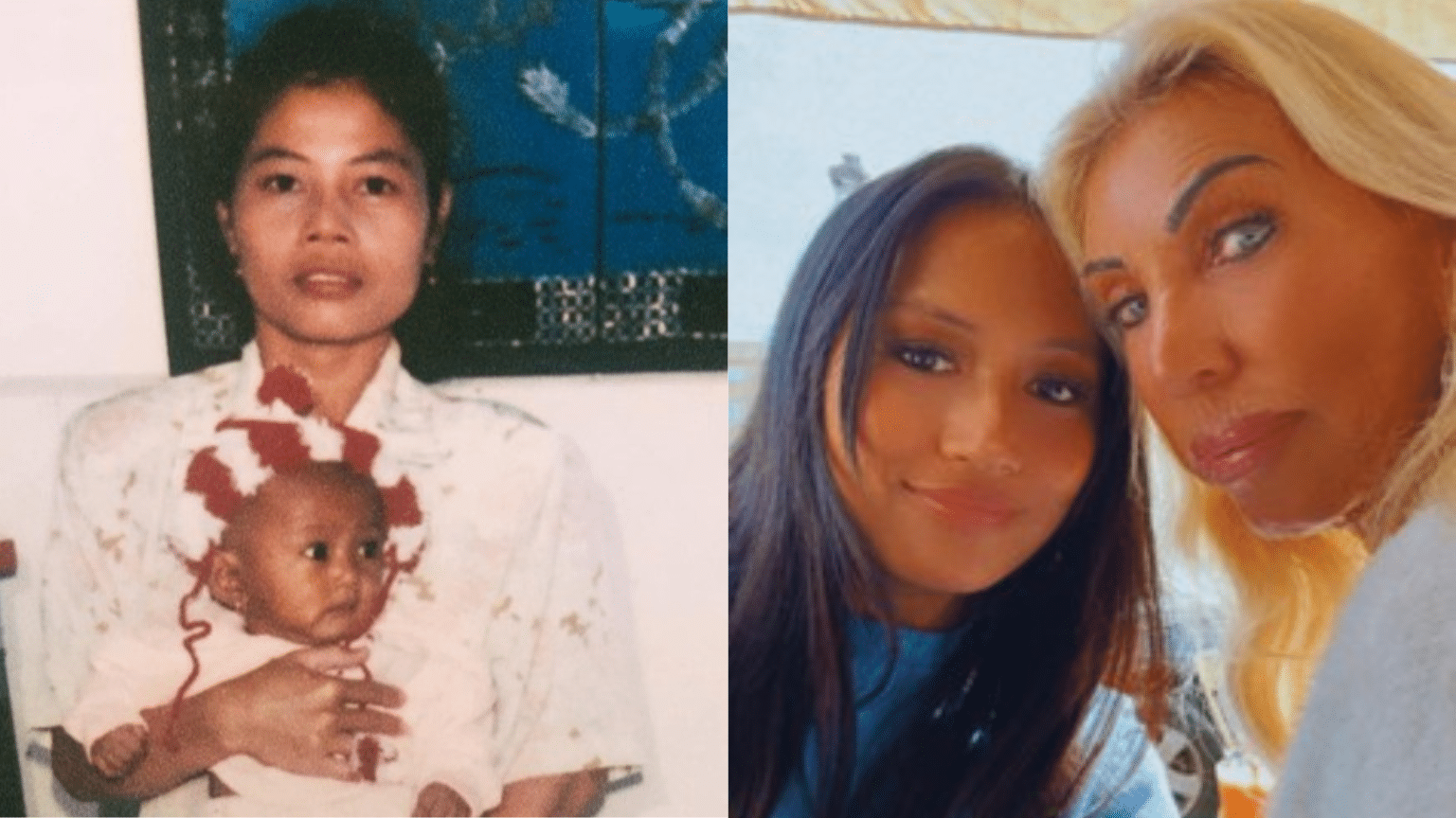

There’s more to tell about the whole reunion process that followed and about what I discovered than I can go into here. But I will say that the fantasies I’d always had about my biological family were put to rest. They were real people. Surprisingly, they were not wealthy, not famous, nor exceptionally attractive. The most important thing that I discovered was my place in the world. I learned where I came from.

I got to know biological relatives who shared most of my interests and had similar world views and personalities. There was a reason why I was the way I was. My knowledge of who I am increased immeasurably after those reunions with biological family members. I refer to the time before I learned about my background as the time when I was anonymous. Twenty years later, it truly seems like another life.

Throughout the whole reunion, my adoptive mother was my unwavering support. She always said, “How can you raise a child from birth and not be curious yourself about their background?” What I did not anticipate, and which surprised me, was how much my relationship with my adoptive mother improved after learning about my background. I no longer felt frustrated at our differences. That need to be like someone was no longer her burden. She was who she was, and she was not like me and that was okay. She’s my mom, and no one could ever take her place.

For me, the decision to search for my biological family was hardly a decision at all. It was a nagging need that had to be met. No matter what the outcome, I knew it was better than not knowing. I don’t have a particularly strong interest in genealogy, though. So, I think, if I were not an adoptee, I probably would not search for information about my great grandparents and other ancestors. No, I don’t think I’d want to search. But then again, that is something I guess I’ll never know.