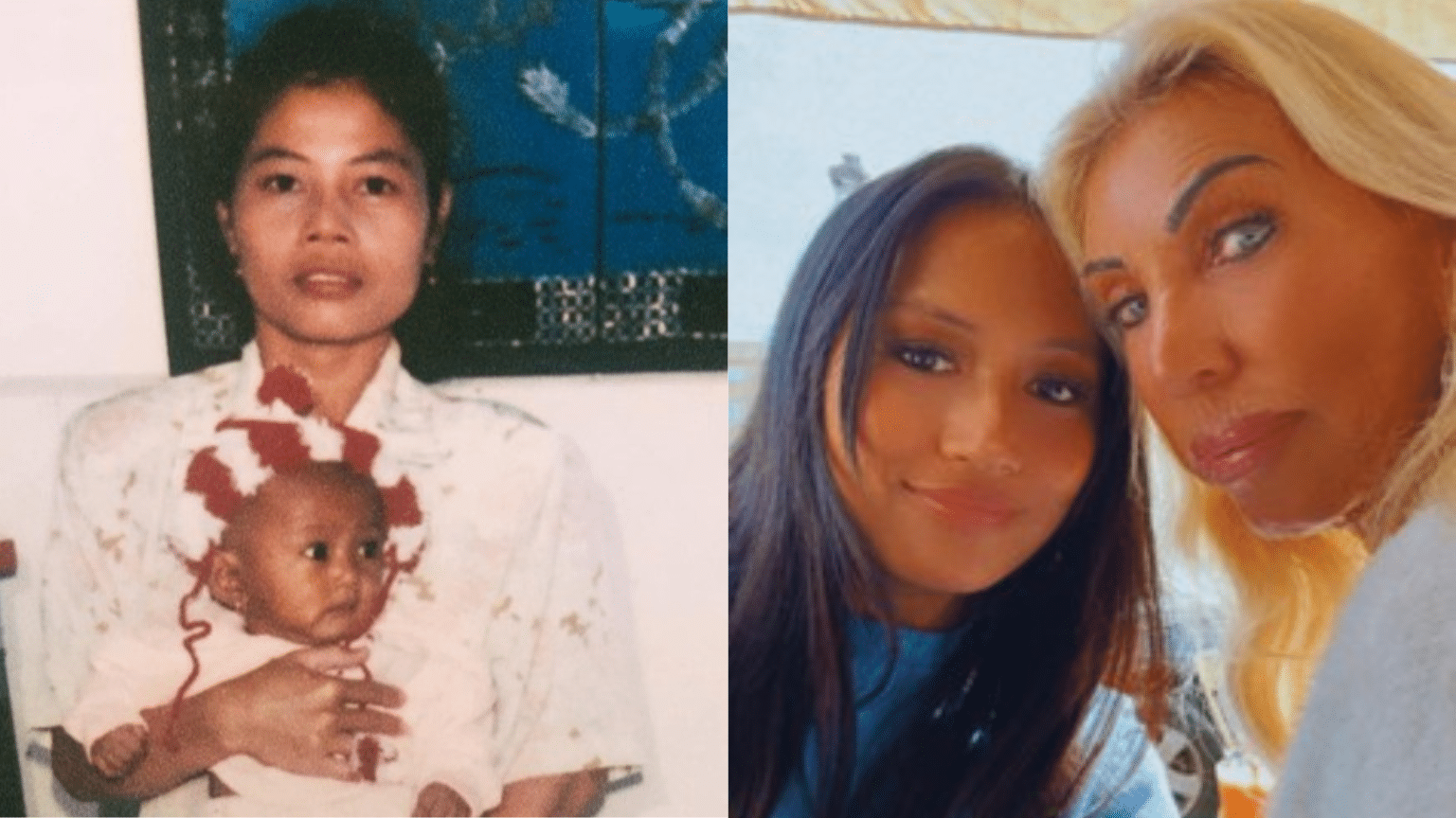

In part two of her story, a birth mom opens up about the intricate realities of open adoption, the struggles of processing trauma, and the vital importance of empathy and understanding. If you missed the first part, you can read it here.

The past caught up with me

It wasn’t until after the birth of my first child in my second marriage that I began to feel the emotional impact of the adoption. I struggled with severe separation anxiety and postpartum depression, finding it nearly impossible to let go of my baby, even for a moment.

That’s when I realized I was dealing with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)—something I had never connected to my adoption experience. When I visited the doctor, he’d say, “Oh, lots of moms experience postpartum depression,” and I didn’t even think to mention trauma. It just wasn’t something anyone talked about, and no one asked me about it.

It wasn’t until I experienced the same overwhelming emotions with each of my pregnancies that I finally understood what was happening. I realized, Oh my God, I have really bad PTSD from the birth and the adoption. I never processed any of it.

The adoption had a ripple effect on my other three pregnancies, my marriage, and my overall life. Adoption impacts so many aspects of life—and so many people—in ways you might never expect.

Balancing trauma and fear of losing connection

The adoptive family moved to the Island too, and our visits began again. I wasn’t prepared for what came next. As my son grew, he began to look more and more like his dad. That was difficult for me because I have very painful, abusive memories of his father. Even seeing those similarities was triggering.

I couldn’t share these feelings with the adoptive family or anyone else, except my therapist. I was too afraid of putting the relationship at risk. My biggest fear was losing that connection.

Even now, when I talk about my experience, I constantly worry: What if they read this? What if they hear something I’ve said about the trauma, about my regrets, or how I believe I should have had the right to say no to adoption?

I’m terrified that they might see my perspective as harmful or unhelpful to their child. And in this situation, they hold all the power. They could cut me off from him at any time.

The challenges of open adoption

Only a few years ago—while my child was already in high school—his adoptive dad told me something that was hard to hear. He said, “You need to understand that she [the adoptive mom] never wanted an open adoption in the first place. She wanted it closed. But when we weren’t getting any placements, we did whatever we could to have this baby.”

It was devastating because I placed my baby for adoption, believing it would be open, happy, and natural. Now, I realize that wasn’t true.

Of course, I love that my child is alive, that I know him, and that he has great parents. But I also recognize the trauma—mine and his. No one likes to talk about how adoptees never consent to adoption and how they must also unpack their trauma.

I have three kids now, and they have a half-brother they barely know. We rarely see him, and the visits are so limited. Last year, I finally wrote all my feelings down and shared them with the adoptive parents. It led to a four-hour conversation full of conflict, emotions, and some understanding. But at the end of it all, the reality hasn’t changed. The trauma is still there. The lack of healing is still there. They still control the visits. That power imbalance hasn’t shifted—and it probably never will.

It’s really hard when actions don’t match words. Hearing things like, “We owe you so much. We love you so much. You’ve changed our lives,” but then seeing none of those actions reflect it, is incredibly difficult. If you truly feel like I gave you the most precious gift on Earth, that should imply things like having a genuine relationship with me. It shouldn’t be transactional.

Would I like to be there for him? Yes, absolutely. I can’t speak for every birth mother, but I don’t think most of us are out there trying to reclaim our child or pose a threat to the adoptive mom. Treating us as a threat, unless we truly are one, is deeply harmful.

My advice is that if that’s not possible, families [prospective adoptive parents] shouldn’t take someone’s baby, especially if they’re unwilling to process the trauma, heal, and build a genuine connection. It’s wrong to take a child under false pretenses, to lie about what you truly want or what the future will look like. A relationship built on empathy, understanding, and connection would make a huge difference.

Navigating trauma

Adoption has been deeply traumatic for me. It brought a level of trauma I could never have anticipated or prepared for, and it feels like something that will carry with me forever. It’s really hard to get people to understand that adoption is anything but simple.

Having a better relationship with him [the child] would help me heal, but I feel like that’s being kept from me. I don’t think I’ll ever fully heal because of how controlled the relationship is.

Processing my trauma has been helpful—it’s not something I treat as a past event anymore. I don’t think there’s a single person for whom adoption, even the most positive experience, doesn’t involve some degree of trauma. There are always layers and complexities. I remember thinking therapy was just for people who were sad and crying, but over time, I realized it’s more about digging deeper and talking things through. What I share with my therapist now is very different from what I said in the beginning. It changes over time, and therapy is never a one-time thing—it’s ongoing.

Having open and honest conversations is also important and can really help. Sharing my story is part of my healing. For years, I suppressed my story out of fear—fear that speaking openly might upset the adoptive couple or result in being cut off from my child. But knowing that my story might help someone, offer a new perspective, or make someone feel less alone is truly cathartic and healing.

Advocating for birth mothers

I believe there’s often a stigma surrounding birth mothers, with the misconception that we didn’t love our children or that we placed them for selfish reasons. In reality, it’s far more complicated. The emotions and challenges are often misunderstood, and there are things you simply can’t prepare for. The experience is traumatic, raw, and complex.

The adoption process needs to be handled with greater sensitivity. Birth mothers should have the opportunity to speak with someone who has been through adoption. In my case, my parents should have been excused from the room at the adoption center, or I should have been brought in alone—the conversation would have been very different. Above all, therapy should be a requirement, not just an option.