Lori Holden literally wrote the book on open adoption (The Open-Hearted Way to Open Adoption: Helping Your Child Grow Up Whole). In this article, she presents a new way of thinking about openness.

How shall we think of open adoption?

I bet if you asked a bunch of people who know about adoption what open adoption is, you would get variations on the theme of contact, that there is a continuum of contact, and that each adoption will find its way on to a point on the continuum.

On one end might be a fully closed adoption, meaning no contact and no identifying information. At the other end people might place full openness—adoptive and birth parents treating each other as extended families.

Seems kinda flat, no?

But as we move into the third decade of the movement toward open adoptions, I submit that we should stop using contact as our measure. Why?

Because contact ≠ openness.

Contact is not the same as openness.

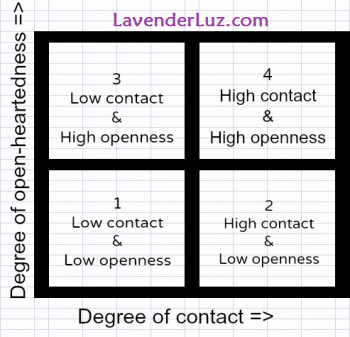

Further, because of the need to consider contact and openness separately, we need a better tool than a spectrum. How about a grid? A grid that takes into account a measure other than contact—the level of open-heartedness on the part of the parents of the child.

Let’s look at each of the boxes.

Box 1: Traditional closed adoption

Not only is there very little contact or identifying information available to the child, but the adoptive parents are ill-equipped to deal with adoption openly. They may have unresolved grief left over from their infertility struggles. Perhaps they were counseled to act as if their child were born to them. They may not be comfortable having tough conversations and confronting “icky” feelings about adoption, either theirs or their child’s as she grows and advances cognitively. This box may be the most crippling for a child to grow up in, the least conducive to integrating her identity from both her sets of parents.

Box 2: Obligatory contact

Here is where there is contact with birth family, maybe through exchanges of photos, emails, or even meetings. Parents here may say things like, “We follow our open adoption agreement and send monthly updates and pictures.” or “We’re not afraid to let the birth parents know where we live.”

What’s lacking in Box 2 is what Jim Gritter calls the Spirit of Open Adoption. Adoptive parents may harbor feelings of guilt, envy, distaste, or even superiority about their child’s birth family, either consciously or subconsciously. (By no means am I saying that all do, but rather I am observing that some do.) These adoptive parents may enjoy having all the power they hold in the relationship rather than inviting the first parents to co-create their open adoption relationship.

Because of the lack of openness here, the child is still at a disadvantage, feeling split between her clan of biology and her clan of biography, for there is quite a gap between them.

Box 3: Openness with discernment

This box is at play in many foster and international adoptions, as well as some domestic infant adoptions where distance or birth family availability is a factor. It involves low contact but high openness.

Logistics and safety issues may make actual contact not possible or unwise, but the parents in Box 3 still parent with openness. They are able to deal with their own emotions about their family-building story mindfully, and they are able to open their hearts to their child as she processes her adoption story and integrates her identity. She is in a good position to have the space and support from her parents to do just that.

Box 4: Extension of family

Here is where the birth family is considered extended family, both in contact and in openness. This relationship may be no different than one with a beloved uncle, sister-in-law, or grandmother (or even a relative not so beloved!).

The relationships are child-centred and inclusive. The child is claimed by and able to claim both her clans, thereby helping her integrate all her pieces as she grows through her toddler and school years, through her tweens and teens and into adulthood. She is not pulled to choose or rank one family over the other and she is therefore not split—she is free to integrate her selves and pursue wholeness in her identity.

Which box is best?

What matters as we set our parenting GPS isn’t where we are left-to-right on this grid. After all, we have only partial control over the level/type/amount of contact. What matters more is the elevation we operate at. The openness required by and afforded to Boxes 3 and 4 is likely to foster healthier relationships than mere contact in Boxes 1 and 2.

Adopting and adoptive parents, where would you plot yourselves? Consider both aspects of open adoption — contact and openness — as you build and sustain a child-centered adoption constellation.

It’s not a contest

Feedback from some adoptive parents indicated that since they can’t fully control the level of contact with birth family, why should they be penalized for being in a less-than-ideal box?

First of all, no one is being penalized. In Adoption World, it’s better to deal with what is rather than what we wish things would be. The boxes are meant to self-assess, not to personalize. I would counsel adoptive parents to focus on openness—what they can control—over contact, which they only partially control. Boxes 3 and 4 are where the benefits of openness in adoption occur, anyway.

One family may have open adoption relationships in more than one box, based on differing situations with birth family members for each child. Plotting can also change over time, as contact and openness can both be fluid.

Lori Holden, mom of a teen daughter and a teen son, blogs from Denver. Her book, The Open-Hearted Way to Open Adoption: Helping Your Child Grow Up Whole, is available in the Belonging Network resource library or through your favorite online bookseller.

This article originally appeared on Lori’s blog, LavenderLuz.com. Reprinted with permission.