For many youth, foster and adoptive homes can be safe places for care and support when the biological family does not provide appropriate care. Unfortunately, many lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youth are placed in foster homes where their caretakers do not understand or accept these youth because of their gender or sexual orientation.

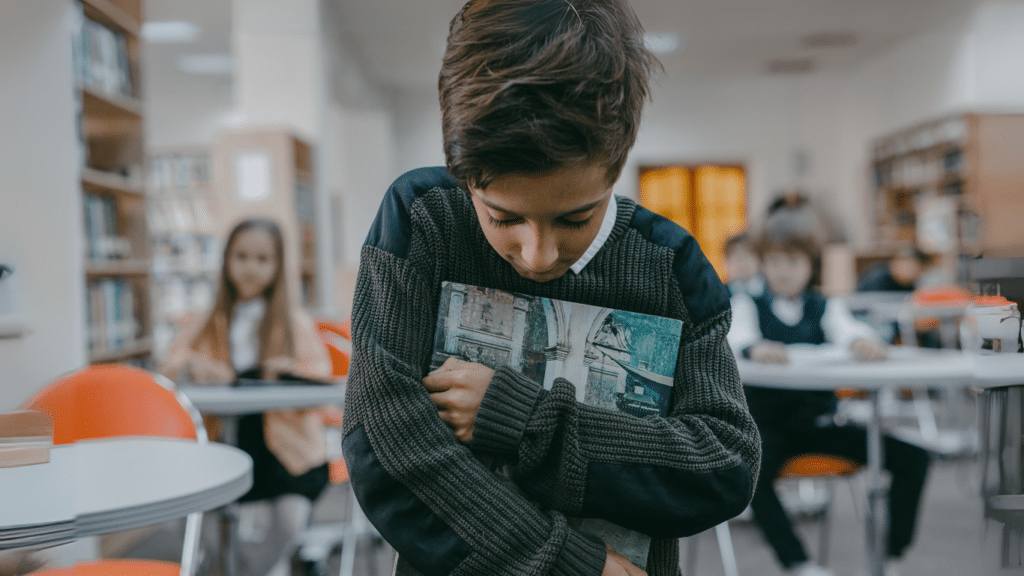

Identity and exploration

An example of an issue faced by some in this population is the experience of a disconnection between their gender identity and their anatomically assigned birth sex. The caretaker must be able and willing to talk about the youth’s feelings and experiences while also allowing the youth to externally express their gender. These youth may also be questioning their sexual identity. Questioning sexual identity refers to trying to understand and accept one’s sexual orientation based upon a physical and romantic attraction to members of the same and/or opposite sex. The foster or adoptive parents must also be willing to protect the youth from other peoples’ judgment or lack of understanding. The parent has agreed to be the youth’s first line of defense against assaults, whether emotional or physical.

LGBT youth may experience a foster or adoptive parent’s inability to talk about their concerns as emotionally and psychologically damaging. If the LGBT foster youth finds the foster or adoptive home environment to be unbearable, they may leave. Homeless LGBT youth may find a supportive and accepting community among others like themselve, but they miss out on a stable and safe home environment, and are vulnerable to substance abuse, sexual exploitation, and incarceration.

LGBT youth who are struggling with self-identification are not in a position to explain sexual orientation to foster or adoptive parents because they themselves are in the process of learning who they are. It’s the responsibility of caregivers to educate themselves about about sexual/gender orientation and how to support the youth they care for. It’s not the LGBT youth’s responsibility to teach them.

Safe families are supportive families

LGBT foster or adopted youth, like all youth, require caretakers who have resolved their adolescent identity issues. They need parents with a strong sense of self and a more fluid approach to self-identity. Parents who are still struggling with defining themselves interfere with the LGBT youth’s identity development.

Youth who are questioning their sexual or gender identity need room to “try on” different orientations. Those who are expressing different orientations may temporarily change their dress, or ask to be called a by a different name or by different pronouns such as he, she, they, or “ze.” The caregiver must be flexible enough to allow the youth to experience a fluid trial period while also providing consistent expectations of behaviour. For example, the curfew should remain consistent and not be considered related to sexual or gender orientation or identity.

Preventative preparation strategies are a crucial component of supporting these youth. The parent must be ready to intervene even when the LGBT foster or adopted youth has not openly identified a concern. The foster or adoptive parents must use their training and experience to identify and respond to any potential emotional and physical assaults to their LGBT youth, and be ready to support and intervene if the youth experiences harassment in their home, community or school.

There’s nothing to “fix”

Foster caretakers must never suggest reparative therapy as an option for LGBT youth. Reparative therapy attempts to change or “fix” a person’s sexual orientation. Good parenting requires accepting and supporting the LGBT youth’s sexual and gender identity. The goal of successful parenting is to help youth define who they are, not who the caretaker wants them to be. Foster and adoptive parents who are not willing or able to learn how to care for LGBT youth are neglectful.

Adolescence is a time of exploration. To facilitate healthy identity development, youth need the emotional, psychological, and physical space and support to explore who they are and who they can become. When a foster or adoptive parent accepts a youth into their home, this acceptance means they are willing to fully care for the youth and their needs, which includes accepting their sexual and gender self-expression and identity.

Barbara Turnage, Ph.D., is a professor and MTC-MSW coordinator in the Department of Social Work at Middle Tennessee State University. She can be reached at Barbara.turnage@mtsu.edu. Justin Bucchio is an assistant professor of social work at Middle Tennessee State University, with expertise in child welfare and LGBT foster youth whose passion for social work and improving the child welfare system stems from his early years in foster care. He can be reached at Justin.bucchio@mtsu.edu