Karen Madeiros, former Executive Director of the Belonging Network, shares her insights as an adoptive mother of two children from the US. Having personally experienced and witnessed the evolution of openness in adoption, she reflects on the valuable lessons learned from her journey.

Why did you open up your adoptions?

Like many prospective adoptive parents, at first my husband and I were hesitant and unsure about openness. In our children’s case, semi-openness initially involved just letters and pictures. But as we gradually learned that openness is not about co-parenting—a fear many adoptive parents have—but about developing a broader kinship network for our kids, we came to see the benefits.

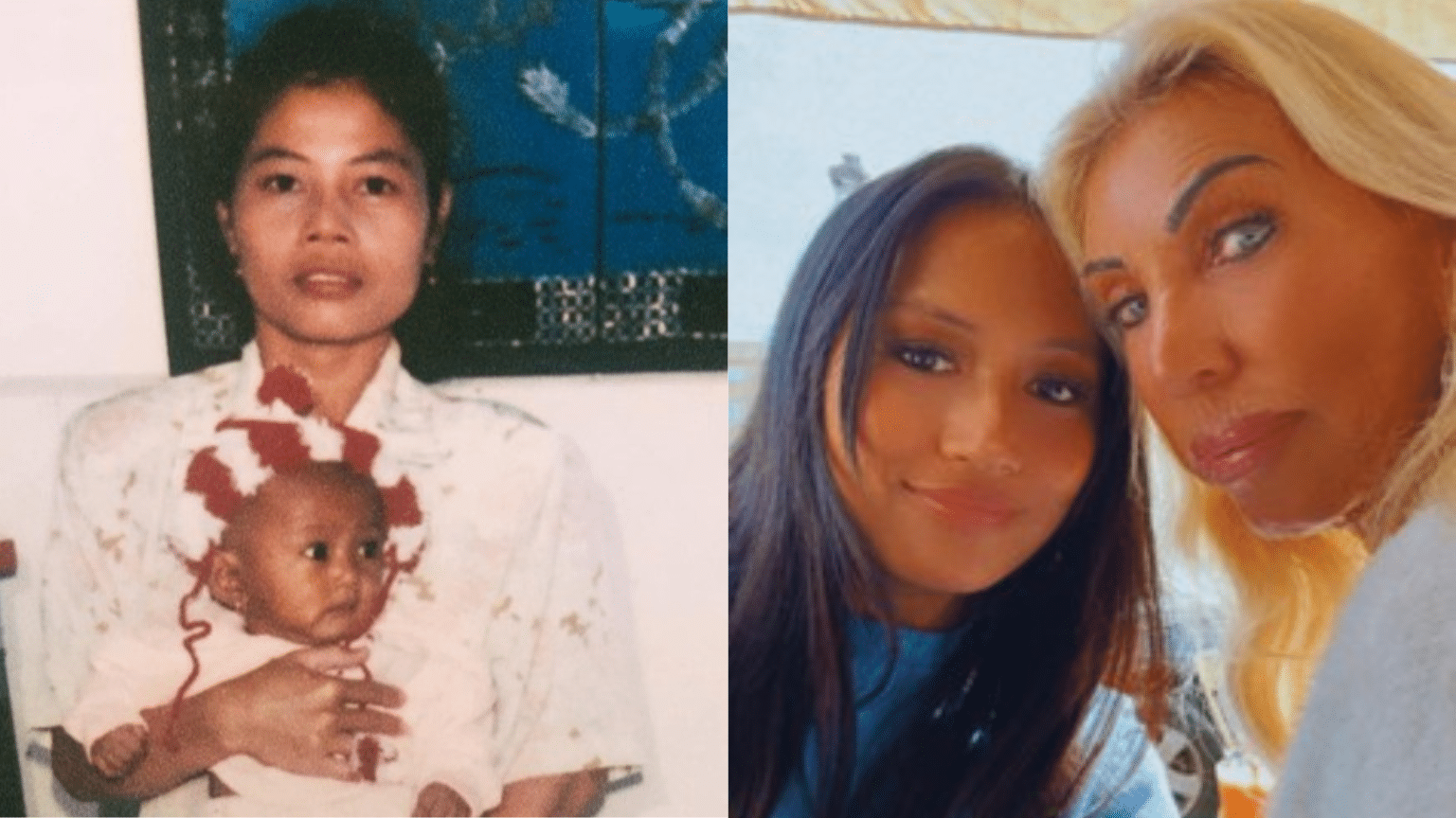

Our now 13-year-old daughter has visited her birth mother and extended family in the US, and her birth sibling visits us. Our son, Garrett, now aged 12, has regular contact with his maternal grandparents and an aunt.

A fear that many adoptive families have is that the birth family will be overbearing and instrusive This is not usually the case.

Something adoption counsellor Kathy Tanner says always comes to mind when I think about openness. She says, whether we like it or not, for children with closed adoptions their birth parents are like ghosts on their shoulders and they are always there. I didn’t want my children to experience that if I had a way of avoiding it. Of course, we have had some interesting times and some very difficult conversations with our kids and our children’s birth families; but never have I wished that we hadn’t embraced openness, and I know that opening up our adoptions has been important in the identity development of my children. I feel that we build our identities like a puzzle. Each piece represents a part of who we are. Kids who have information about who they are and where they came from can incorporate this information into their puzzle at an earlier stage. It can be devastating to learn critical information at a later date and then have to pull their identity puzzle apart and maybe even have to take pieces out.

These days, adoption professionals are doing a much better job at making sure that children have information about their background—but there is no substitute for information directly from birth family.

How was the process?

It wasn’t easy. Nearly all the work falls onto the shoulders of the adoptive parents. In our case, just finding the birth parents and establishing connections took a lot of work. Then, of course, we had to take the time to prepare ourselves and our children for the eventual meeting with them.

Part of the process in opening up an adoption is doing a good assessment of what is known about birth family members and identifying which members would be most receptive or positive—sometimes this is not the birthmom. This turned out to be the case with one of our children.

The second step is developing the adult-to-adult relationship with the birth family. This can involve months of writing and telephone calls to get to know each other and to ensure that everyone understands the boundaries and expectations. I would suggest that when openning up an adoption some of this be done without your child’s knowledge.

In a way, I see openness as a bit like drawing a picture of a child and then placing around it all the people who are important to that child. Adoptive parents must figure out who amongst those people is willing, able, or most appropriate to become involved. That can look very different for each person.

Of course, a fear that many adoptive families have is that the birth family will be overbearing and intrusive. This is not usually the case and discussions beforehand can really help to avoid that. We need to work with birth parents on expectations and boundaries for both parties. Most birth parents worry about doing something wrong and jeopardizing the relationship. They know that all the power is with the adoptive family. We have to encourage them and give them permission to be involved. If the birth family is intrusive, it’s up to the adoptive family to reaffirm the boundaries and make them clear.

What is openness?

I feel that openness, in its broader context, is really a state of mind. Although a family may choose an adoption route that is traditionally closed, like China or Russia, they still need to have an openness of mind in raising their kids. While finding information or keeping in contact with birth family may be very difficult, or even impossible, parents can still embrace their children’s culture, talk about their birth family and the child’s early experiences as much as possible.

The idea that adoptive children come to us as a blank slate is history. An important piece of work is to get prospective parents to understand that adoption today is about parenting kids who have two sets of parents and extra family members. Adoptive families have to truly embrace the idea that we don’t own our children—which can be difficult.

In fact, I see two processes in openness. The first is getting prospective adoptive families to embrace the benefits of openness for their kids and themselves. The second is figuring out how to do this for their particular situation. Of course, the process is not always smooth or predictable; some families are very receptive to the idea of openness, but for various reasons it just doesn’t happen. Others don’t embrace it and then find themselves having to accept some measure of it.

The challenges

As parents we do a lot of things for our kids that we don’t really want to do—for some adoptive parents openness is one of those things. It should not be done in a half-hearted way. If it isn’t a genuine attempt at forging a meaningful relationship for our kids, then it won’t be meaningful for them.

Openness can be hard for new adoptive families because it often feels like it’s happening to them overnight. They have to learn to embrace the concept fairly quickly. Unlike many other cultures where broader kinship networks are well established and taken for granted, many Canadians find it difficult to welcome people into their lives with whom they have no previous connection. There is a high probability that the lifestyles of the two families are not going to be a perfect match, but we can find ways to navigate around this. We all know how to involve people in our lives who live differently to us. Look at most families and you will see this process of working out relationships—we make the effort to do it.

There can be many surprises in openness. For instance, I know of one family where the adoptive parents do not leave their children alone with their own parents but happily do so with the child’s birth grandparents.

We have to ask adoptive parents to be more open-minded and daring than other parents. Living openness is the biggest challenge next to parenting that we ask of adoptive families. Openness asks them to go to fearful and scary places—but it can also bring rewards.

However, in the swing of the pendulum from closed to open adoption, I do worry that we’re moving to a definition of openness that includes an expectation of “contracted” contact. This can be the case with some adoptions where adoptive families literally sign a contract undertaking to maintain openness at a specified level. AFABC has been hearing from parents who find this tremendously difficult, not because they don’t believe in the value of openness, but, because they feel that that level of contact interferes with their ability to bond with their child or because the contact is negatively impacting their child. I am hearing about situations that I personally would be very uncomfortable with—even though I’m a huge proponent of openness.

It’s all about balance. We must allow parents to make judgments about what is best for their child and trust that if they are seriously concerned about the level of openness that they originally agreed to, then they should be able to revisit that agreement.

Finally, I would say that openness is not a panacea for all that ails adoption. But it can provide children with information that they need, allow them to build important relationships, and ultimately save them from some of the pain of research and reunion as adults.