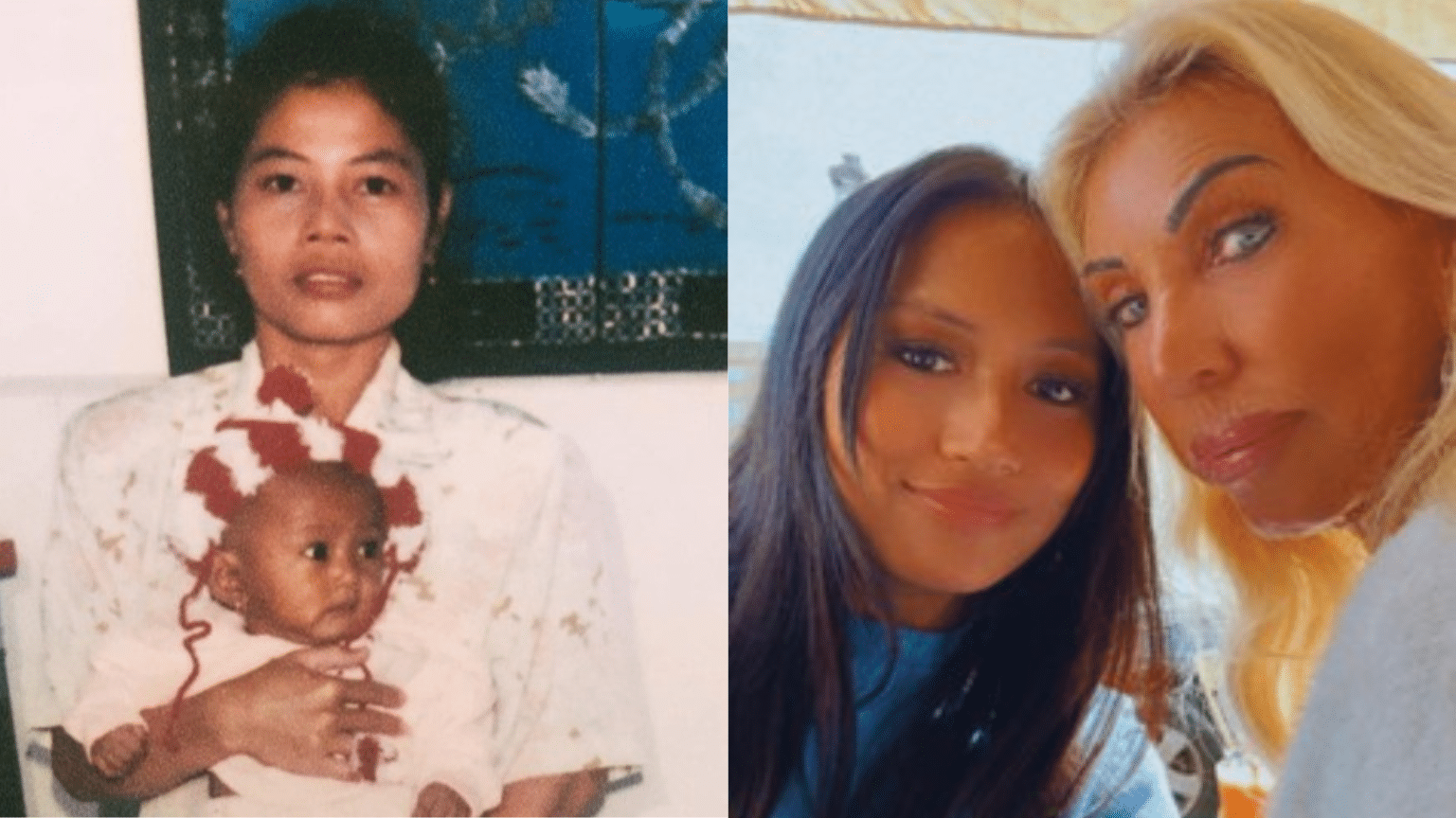

In this honest and heartfelt story, a birth mother opens up about her adoption journey. She reflects on growing up in a strict environment, feeling voiceless, and how adoption, while meant to offer hope, also brought deep emotional struggles. Her story is a reminder that adoption is not simple—it’s often filled with complex feelings and lasting impact.

Growing up voiceless

I was raised in the Mormon Church. My parents were both very religious. Growing up in that culture meant living under strict rules. I was taught to ignore my body and intuition, with shame surrounding topics like sexuality. Conversations that should have been open were dismissed or ignored. I had three environments—home, church, and school—where my voice didn’t matter. I had very little autonomy, whether it was over my body, my emotions, or anything else.

I went to a Mormon university in Utah. There, we were told explicitly that boys were there to get a job and an education, and girls were there to find a husband. You were expected to do this before graduating. My best friend and I got married. I divorced within a year.

After the breakdown of that relationship, I started working at a company where many of us had grown up Mormon. Now, as adults outside our parents’ control, we were figuring out who we were. None of us had experienced choice or autonomy growing up.

I became involved with someone who, looking back, was grooming me. At the time, it felt like freedom—I was no longer under the Mormon agenda or my parents’ control. This person suggested we run away, get married, and start a family. I was young and naive, excited by the idea of this kind of relationship. But what started as a fun, charismatic relationship quickly turned abusive, controlling, and manipulative. I got pregnant, and soon after, the control, abuse, and aggression escalated—to the point where there were threats to my life and the baby’s life.

I called the only people I could ask for help: my parents. They drove down to Utah to pick me up in the dead of night. As soon as we were in the car, the first thing they said was, “We know who you’re going to give your baby to.”

Adoption was the only option

I knew that whatever my parents said was going to happen. I knew that my voice didn’t matter. I was told that no one would want to marry me if I had a child from a previous marriage, that you need a Mormon mom and dad to properly raise a child, and that single moms can’t do that. These beliefs were deeply ingrained in me.

I was coming out of an abusive situation and then brought home with the idea that I was safe now—that God would take care of me. My parents made me feel like they had the solution, feeding into the belief that to redeem my soul from the mistakes I had made, I needed to give my baby to a more faithful, righteous couple in the church.

Now I know that’s very manipulative, but at the time, that’s not how I saw it at all. I just thought, Oh, thank goodness. I’m not going to hell. Thank goodness someone’s going to solve this problem for me.

The adoption process

My parents reached out to a couple in my extended family who are related by marriage, and they came over. It was just like, “Here’s our daughter, and she has your baby.”

I remember having a few meetings at the adoption service center. I was always with one of my parents. I was never alone. No one ever asked me if this was something I wanted. Later, I realized that even if they had, I don’t think I would have been honest—because saying no or voicing my opinion never felt like it mattered.

During the adoption process, the [adoptive] couple was lovely and attended every appointment. I genuinely thought we had built a natural, wonderful friendship. At the time, I had no friends or strong relationships at home, so I was thrilled to have kind, loving people in my life. It made me feel like adoption was a good thing.

We had a meeting about the birth plan, and I knew what I wanted. I wanted the couple to be there, along with my family, so we could talk, exchange gifts, and share that moment together. I had an idea of how it would go, but then they presented their post-adoption plan: a detailed document about how often I’d receive photos and updates, from zero to two years old, then two to five years old. We were both expected to sign it. I remember feeling gutted as if it was a contract rather than something organic or friendly. It was the first time I felt uncomfortable with the situation, but I didn’t feel like I could say anything.

Facing struggles alone

A few months before the birth, my dad came to me and said, “Your mom wants you out of the house. If you don’t go, she’s leaving, and we’re getting a divorce.” People are often shocked to hear that, but it was my reality growing up—dysfunctional and chaotic.

At seven months pregnant, planning to give my baby up for adoption, I was being kicked out. I ended up alone in an apartment in West Vancouver. I was deeply suicidal, battling severe depression and anxiety.

Even then, I kept telling myself, I couldn’t let these people down. They’re counting on me to give them this baby. I forced myself to stay alive, despite everything, because I didn’t want to disappoint anyone.

The birth

I was staying with a woman connected to the Mormon Church’s adoption agency in BC and went into labour at her home. During the birth, it was just her and one of my siblings. The social worker didn’t work weekends, so she wasn’t present.

My child was born the next morning. I was high on adrenaline, and holding my baby felt magical. I remember hearing the nurses whispering that I was giving up my baby, advising each other not to let me breastfeed because they worried it might make me bond with him. I definitely wanted to breastfeed, but they told me not to.

For a brief moment, I thought, I love this baby. This is so great. I feel happy. But then I realized it was too late. I thought, I’ve made this commitment and this promise, and I don’t want to cause all this hurt and pain.

I called the adoptive family a few hours after the birth. Handing over my baby felt like giving away half of my body. I walked out of the room and turned to see them huddled together, crying tears of joy around the baby.

Leaving the hospital alone was one of the most painful experiences of my life. I was physically hurting, bleeding, and emotionally drained. I felt used. Walking out empty-handed, I realized everything had changed. They no longer needed me. This was never about me—it was always about the baby.

“Moving on and putting all behind me”

I returned to the woman’s house and told my sister, “I need to get out of here. I can’t just sit around imagining what my baby is doing and waiting for them to call.” So, my sister and I left. We went backpacking in Europe for four months, trying to distract myself and pretend it was all behind me. In some ways, it worked—my body healed, my milk came in and went, and it started to feel like nothing had happened.

When I came back to Vancouver, my church leaders told me not to talk about it. They didn’t want anyone to think that what I had done was okay. They even gave me a book called The Sin Next to Murder, about having sex outside of marriage. They saw me as someone who needed saving, and I believed that too. That narrative stuck with me for a long time.

The adoption agency suggested I go to therapy to process everything. At the time, I didn’t feel I needed it. I had started my teaching degree at UBC, and was making friends, dating, and moving on. I thought, They have the baby, I know he’s safe and healthy, and I’m moving on with my life. I don’t have anything to talk about. After a couple of sessions, I stopped going and put it all behind me.

I moved to Vancouver Island and got married. My visits to the adoptive family became less frequent.

The journey doesn’t end here. In the next part of the story, the birth mom shares her perspective on navigating the realities of open adoption, processing trauma, and the vital role of empathy and understanding in healing.